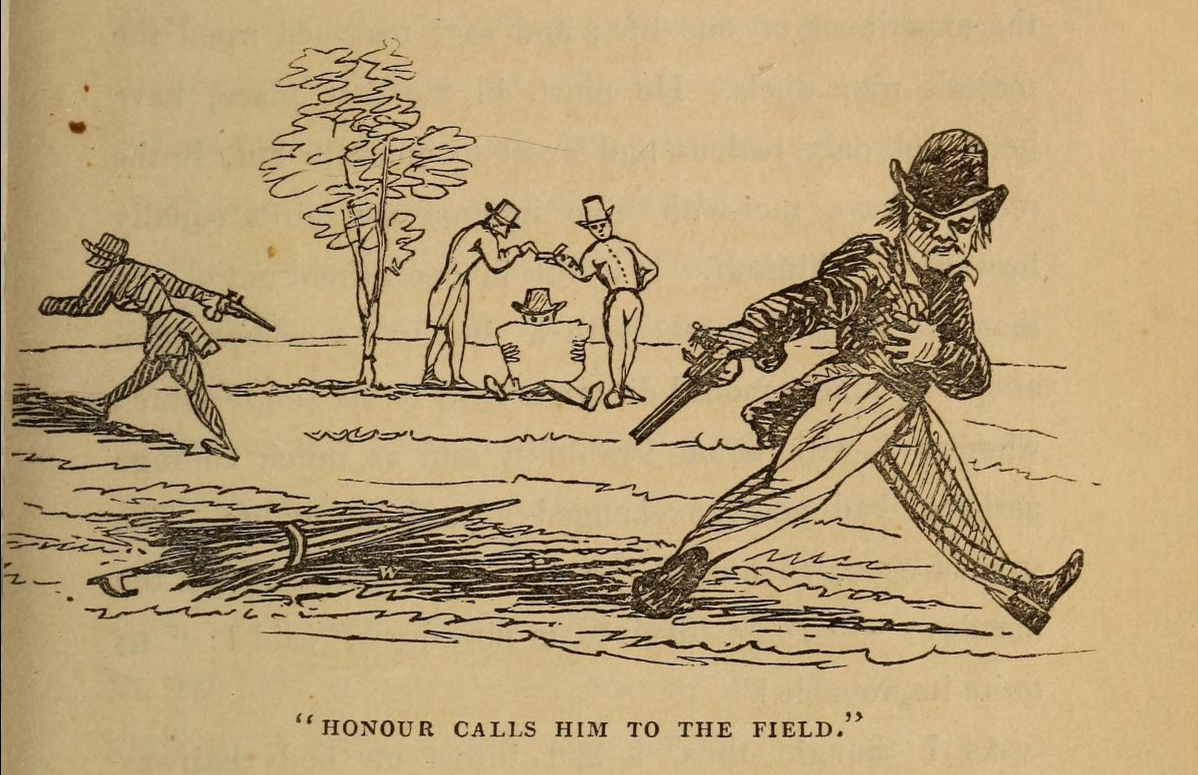

‘Honour Calls Him to the Field’ from Whims and oddities : in prose and verse, by Thomas Hood, London 1836, p342, The Internet Archive

Did you know a duel took place in a field in Homebush early one morning in March 1827? Dictionary of Sydney contributor Catie Gilchrist has written a fascinating article about the ceremony that was used to settle disputes among gentlemen in colonial Sydney. I spoke about it this morning with Nic Healey on 2SER Breakfast.

Duelling revolved around a code of honour; ‘honourable’ men could never refuse a duel, yet to accept could result in their death. After a clash between the two gentlemen, calling cards or letters were exchanged and if the matter could not be settled verbally, a duel was called. And this question of honour was not just at the heart of the duel ceremony, it was also what often caused these disputes to occur in the first place. Sydney was a small town, where gossip and rumour flourished and so offences against a person’s character were seen as quite a serious act. The first duel took place between surgeon John White and his assistant William Balmain in 1788, It is not clear what caused it but they were both wounded during the fray.

Early one morning in March 1827, Henry Dumaresq, the personal assistant and brother-in-law of Governor Ralph Darling, met Robert Wardell, a barrister and an owner of the Australian newspaper, in a field in Homebush. The pair attempted and failed to shoot each other three times from 30 paces. In the end, Wardell offered a verbal apology to finally settle the matter. Dumaresq accepted and the parties mounted their horses, ‘courteously saluted each other and rode back to Sydney and breakfast’. This had not been the first duel for Wardell, however, who a year earlier had challenged Attorney-General Saxe Bannister to a duel at Pyrmont after Bannister had called Wardell the ‘scum of London’ during a speech in court.

Not all duels ended with both parties escaping unscathed. In April 1828, Charles Penberthy, a chief officer on the female convict ship Elizabeth clashed with Robert Atkin, also on the ship. They met the next morning on Garden Island with loaded pistols. After two misfires, the third shot from Atkin struck Penberthy, who later died of his wounds aboard the ship. Atkin was tried and found guilty of manslaughter as the judge did not take kindly to their reasons for duelling:

To proceed to such extremes as these, to satiate the ebullition of passions arising out of angry feeling, is false honour…You permitted yourself to be hurried on this step by an impulse of feeling which the giddy world is apt to say, arises out of injured feeling, and to resent what you conceive an insult – you satiate that resentment by causing a fellow creature’s death.

In general, juries rarely convicted duellists if it was felt the code of honour had been upheld and the notion of ‘honest violence’ or a fair fight was satisfied. Magistrate James Charles White for example, refused to return fire because his opponent had been drinking all night and was not ‘fair game’.

There were descriptions of duels published in the newspapers of the day, the Sydney Herald reporting in September 1831 of one taking place on Garden Island and the combatants returning safely back to shore ‘in the same boat. The cause of the duel arose from a misunderstanding at cards’.

One of the last famous duels took place between the surveyor Thomas Mitchell and Stuart Donaldson, later the first Premier of NSW, in Centennial Park in 1851. Three shots were fired and both emerged unscathed. The duelling pistols Mitchell allegedly used in the fray are now at the National Museum of Australia.

Listen to my segment at 2SER radio. For other interesting segments, see my Dictionary of Sydney project post and visit the Dictionary of Sydney blog.