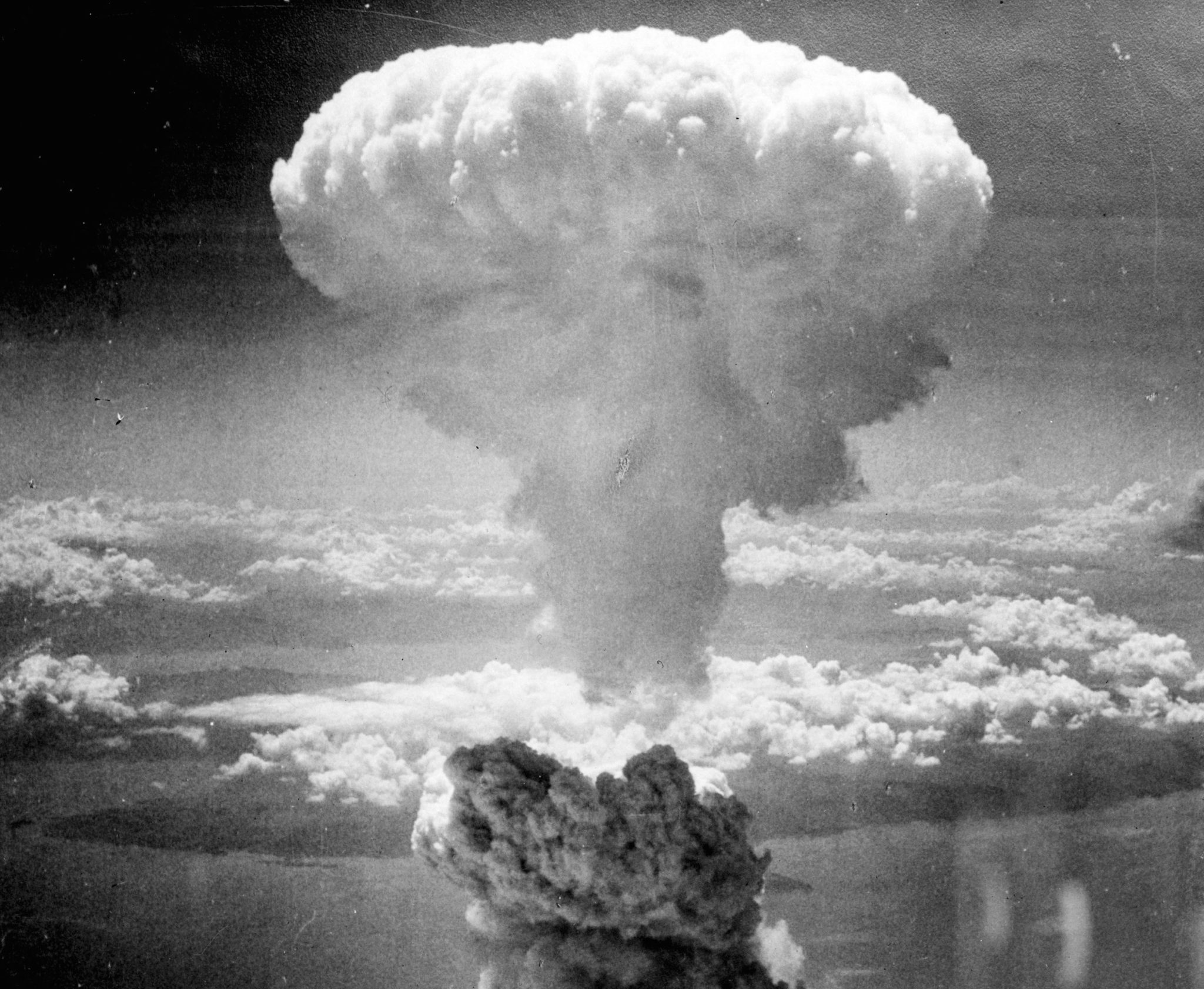

The mushroomed cloud of the atomic bomb dropped over Nagasaki, 9 August 1945. Photo taken by Charles Levy from one of the B-29 Superfortresses used in the attack. Wikimedia Commons

It’s 70 years since the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. As the bombs fell and killed an estimated 250,000 people, Sydney-born author Elizabeth Kata was interned in the mountain resort village of Karuizawa. The Dictionary of Sydney has more about her amazing story of love in a hostile world and her attempts to fight racial intolerance, an issue that continues to be relevant today. I spoke to Mitch about her story on 2SER Breakfast.

Elizabeth Kata was born Elizabeth McDonald in 1912 and spent most of her life in northern Sydney. In 1936, Kata met the Japanese concert pianist and her future husband, Shinshiro Katayama, while he was studying in Sydney. Her family encouraged their relationship and by the following year, the couple were living in Tokyo, Japan.

Elizabeth Kata, Australian Women’s Weekly, 1961. National Library of Australia

Before World War 2, Kata experienced a privileged life in the bustling capital city, however, after Pearl Harbour was attacked in 1941, her situation changed dramatically. According to Damian Kringas’s article in the Dictionary, of the 41 Australians interned in Japan, it is believed there were only two women – one of them was Kata. She initially spent time teaching English in a high school, but as conditions deteriorated, she and her husband were moved to the mountain resort town of Karuizawa. In an interview in 1963, she said ‘those four dreadful years taught me how to appreciate peace and to hope that one wonderful day the world will really be peaceful’.1’Elizabeth Kata interviewed by Hazel de Borg‘, 7 May 1963, National Library of Australia

Though they were safely tucked away from the major cities, the winter was harsh and the food supply dwindled. Then, three weeks before the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Kata gave birth to her son David. She would later tell the Australian press she received no help from the Australian government in her desperate predicament.

In 1947, Kata managed to return to Sydney with her son David. Their return was reported widely, with many Australian newspapers reflecting the hatred felt for all things Japanese. Some made pointed remarks about her son’s appearance, describing him as ‘dark -haired’, ’dark-eyed’ and ‘olive-skinned’.2’Australian Wife of Jap Returns‘, News, 24 March 1947, p. 7 ; ‘Praise for Japanese Family‘, Truth, 2 March 1947, p. 35 Others made more overt racist and offensive remarks and in the time that followed their return, Kata would campaign to have her son become an Australian citizen.

Elizabeth Kata and her young son, David, arrive in Australia, Sunday Times, 1947. National Library of Australia

Her first novel, Be Ready with Bells and Drums, was written from her Mosman home in 1959, and details the story of a blind girl who falls in love with an African American man. Her book became very successful, was published in different languages and adapted into an award-winning film called A Patch of Blue (1965). Although she was the first Australian writer to have a work adapted to an Academy Award-winning film, Kata did not receive significant royalties for her work.

Kata continued to write for film and television both in Australia and overseas. Two of her books were directly influenced by her experiences in Japan. She and her husband never reunited, though they remained close and she regularly travelled to Japan. Kata died at her Sydney home in 1998. Her famous first book was used in schools in Australia and the United States as part of a curriculum aimed at developing racial tolerance. She said in 1963:

I’ve always thought very deeply about racial intolerance, to me its the greatest pain and greatest sorrow in this world today, worse than anything that ever has been.

Her words ring true, even today.

Check out the original article at the Dictionary of Sydney and listen to my segment at 2SER radio. For other interesting segments, see my Dictionary of Sydney project post and visit the Dictionary of Sydney blog.

References

| ↑1 | ’Elizabeth Kata interviewed by Hazel de Borg‘, 7 May 1963, National Library of Australia |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ’Australian Wife of Jap Returns‘, News, 24 March 1947, p. 7 ; ‘Praise for Japanese Family‘, Truth, 2 March 1947, p. 35 |