An early 20th-century cigarette card – even more collectable now than it was back then – depicts the mesmerising Australian swimmer and star of stage and screen, Annette Kellerman. Nicole Cama was inspired by the card to explore this aquatic actor who took her world by storm.

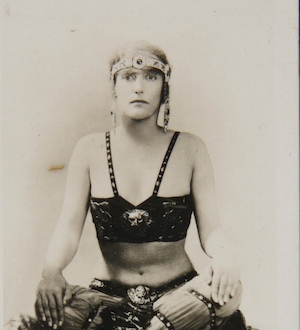

Cigarette card with photograph of Annette Kellerman in costume from the flm A Daughter of the Gods (1916). It was one of a series of 50 ‘beauties’ being distributed with this brand of cigarettes. ANMM Collection.

WHEN YOU THINK of the macabre images associated with cigarette packaging today, they couldn’t be further removed from this photograph of the famous Australian swimming star, Annette Kellerman. It appears on a cigarette card featuring a promotional still of Kellerman in her leading role in the 1916 film, A Daughter of the Gods. With her confident pose and revealing costume, it captures some defining elements of Kellerman’s celebrity status. Much has been written about the mystique and heroism of the star who was christened the ‘Diving Venus’, ‘Neptune’s daughter’ and ‘the perfect woman’. This image reinforces these labels, but it underplays her important contribution to women’s swimwear, health and fitness.

Annette Kellerman was born in Darlinghurst, Sydney in 1886. She spent part of her childhood in Marrickville before catching what she called ‘mermaid fever’ when she learned to swim at Cavill’s Baths in Lavender Bay, North Sydney. As a teenager, she won her frst NSW championship in 1902 and performed swimming demonstrations in Melbourne Aquarium, inspiring one journalist to proclaim, ‘she will become the rage of the town’. She moved to England with her father in 1904, swimming the Thames, the Danube and the Seine and becoming the frst woman to attempt the English Channel. In 1906 she went to the USA where she performed a range of diving and swimming techniques for audiences in Chicago and Boston. The media interest she attracted fuelled her ambition to take her aquatic talents even further, to a stage career in vaudeville theatres and then in silent cinema where she performed a range of roles including the mythical mermaid, mysterious beauty and assertive heroine.

Tobacco cards like this one from our collection emerged in the mid-1870s and were used as cardboard stiffeners for paper cigarette packages. By the 1880s they had evolved from this basic function to become an important promotional medium for a nascent advertising industry. An early version of ‘product placement’ in reverse, they appealed to the human collecting impulse to build brand loyalty. The images they featured ranged from British architecture to boxing champions and even poultry. Cigarette cards, today highly collectable though still a little quaint, are examples of the way popular culture manifested itself in everyday consumer products.

This brings us to the early 20th-century tobacco card featuring Kellerman at the height of her fame, as the exotic beauty Princess Anitia in A Daughter of the Gods. Although the flm itself has not survived, at the time it was the most expensive Images such as the one on this cigarette card demonstrate how Kellerman responded to the social and cultural values of her day film ever made and it is today considered to be the frst movie to feature a major star – Kellerman – in the nude. Media reports during Kellerman’s career reflect her flourishing celebrity status. Described as the ‘wonder woman of the water’, journalists praised her ‘versatile’ and ‘original’ performances. Dr Dudley Sargent, a lecturer at Harvard University, famously concluded she was physically ‘the perfect woman’ and ‘a good model for young women’.

Despite the media hype, Kellerman’s mermaid routine waned in popularity. One reviewer cynically described her film Queen of the Sea (1918), as ‘rather poor entertainment’ and an ‘impossible fairy tale’ designed to display Kellerman’s aquatic talents which were, by that point, outdated and earned no more than ‘a wan hand’. But as Kellerman would go on to prove right up until the late 1920s, there was still ‘none more shapely or talented than Annette’.

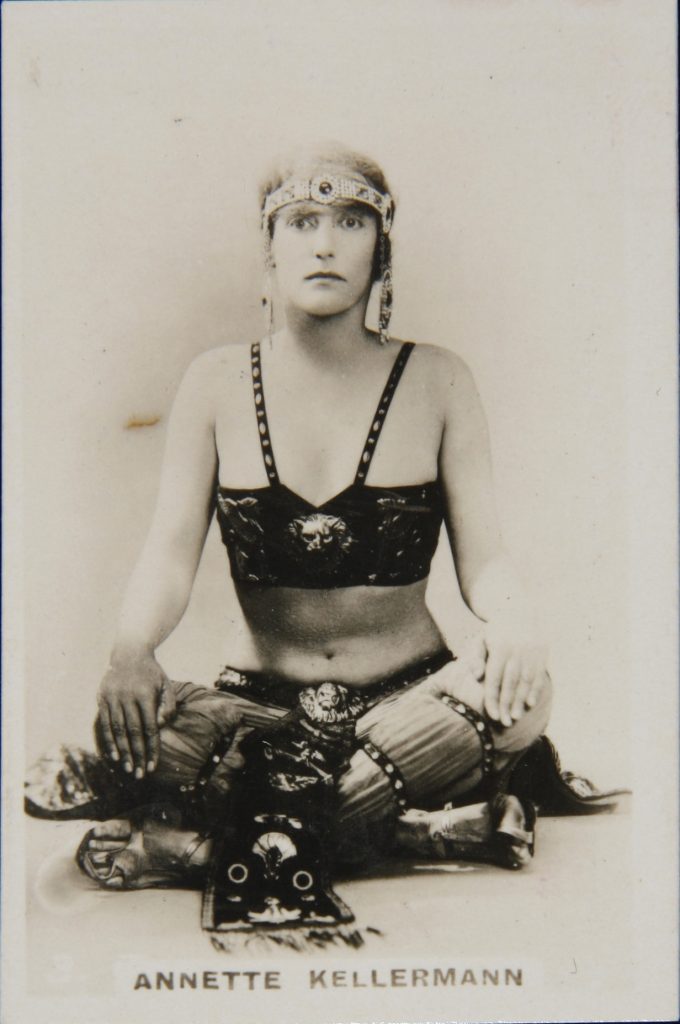

Studio portrait of Annette Kellerman, about 1907, wearing a one-piece Canadian-style costume, headscarf, arm jewellery and anklet. ANMM Collection.

This cigarette card represents, in microcosm, celebrity as the packaged commodity. It is a pocket-sized image of a famous screen goddess, easily accessible and strategically marketed to the early 20th-century gentleman. There are a range of photographs of Kellerman in her numerous guises, usually emphasising her athletic prowess. This publicity still depicts Kellerman at her most direct, confident and sensual, staring unflinchingly at the viewer. Despite her sensuality, such promotional images were also designed to appeal to women. Kellerman was proposed as the physical standard for all women, and what she wore was an important aspect of her publicity machine. Kellerman encouraged this exposure, commenting in a 1910 interview: ‘I believe in being original … People used to stare and laugh – but they paid attention’.

Provocative images of Kellerman acquire even more significance within a social and cultural context that espoused moral decency, propriety and a tightly defined femininity. Kellerman played a significant role in objecting to what she termed ‘prudish and Puritanical’ ideas about women’s swimwear. She criticised ‘Dame Society’ and the ‘pseudo-moral’ restrictions placed on women, and advocated more practical swimsuit designs. Her customised ‘union suit’ and the one-piece men’s swimsuits she promoted, embodied the clash between traditional values and the spontaneous drive for individuality. Early in her career, she tapped into a market teeming with women who she claimed were ‘mad on the beauty question’, and lectured on women’s health and fitness. In 1918 she published two books, Physical Beauty and How to Keep It and How to Swim. While often self-referential and self-congratulatory, there are other messages to be gleaned from their pages centring on the importance of women’s health.

Images such as the one on this cigarette card demonstrate how Kellerman responded to the social and cultural values of her day

Though undoubtedly a talented swimmer, Annette Kellerman was the consummate performer, morphing into many personas to suit the context and audience. She captured the mystery of the female form, which she used to her advantage through revealing costumes and clingy swimsuits. Underneath the surface, however, were messages about women’s health and the need for practical swimwear designs. Images such as the one on this cigarette card demonstrate how Kellerman responded to the social and cultural values of her day, and how she sought influence in ways that were available to her. Whatever the truth or fiction behind the persona, one fact remains clear: Kellerman challenged social and cultural boundaries.

For her, swimming fed the ‘imagination’ and allowed her to escape and ‘forget a black earth full of people that push’. Through various media, she displayed how the streamlined swimsuit or the exotic costume represented freedom and vitality. This tobacco card exhibits the intensely commercial nature of the movie star and, in an ironic way, the product it promotes contradicts the messages of health and fitness that Kellerman endorsed. But more than just a symbol of the cult of celebrity or a relic from an era when smoking was a glamorous pursuit, the card remains a lasting tribute to the mermaid who made waves of her own.

NOTE: This story was originally published in Signals magazine, Issue 99, Jun-Aug 2012, pp 60-61. Reproduced courtesy of the Australian National Maritime Museum.