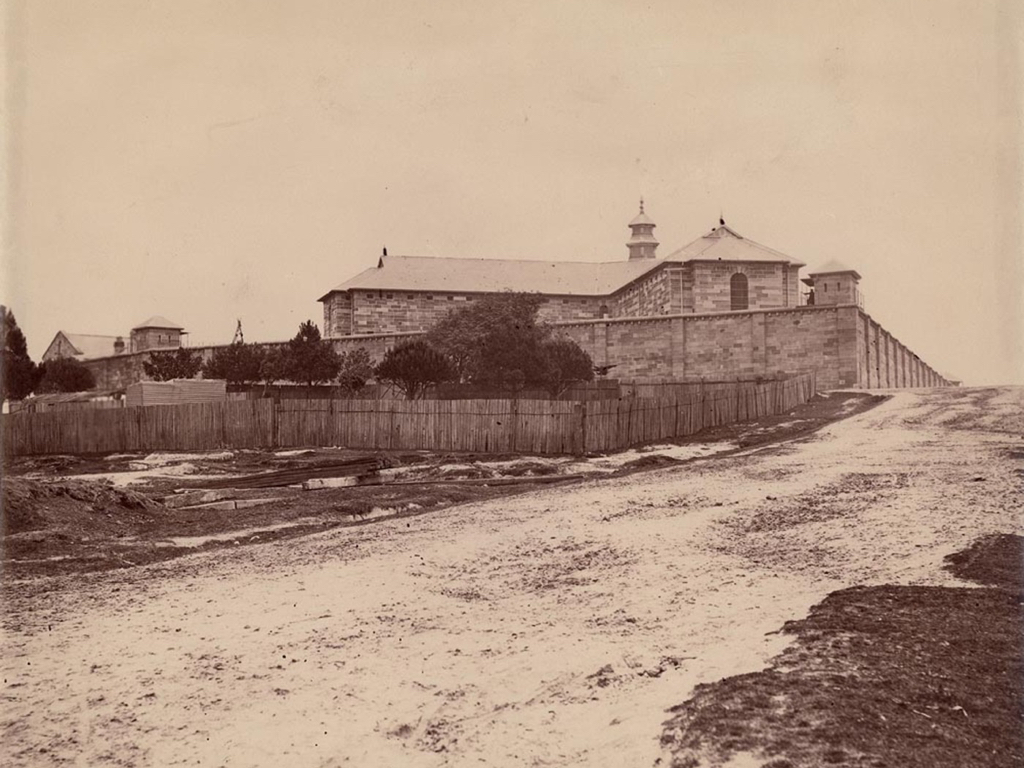

Entrance to Darlinghurst Gaol, 1887. State Library of NSW

At about 20 minutes to nine on the morning of 8 January 1889, the grand iron gates to Darlinghurst Gaol were opened to five representatives of the metropolitan daily press. A large crowd assembled outside the gates awaiting the day’s highly anticipated private execution of what the paper’s called, the ‘Botany murderess’. Among those gathered were what one journalist termed, people ‘the stews and dens of the lowest city life had sent out’. But there were also respectable members of society, men and women who brought their children to this morbid non-spectacle.

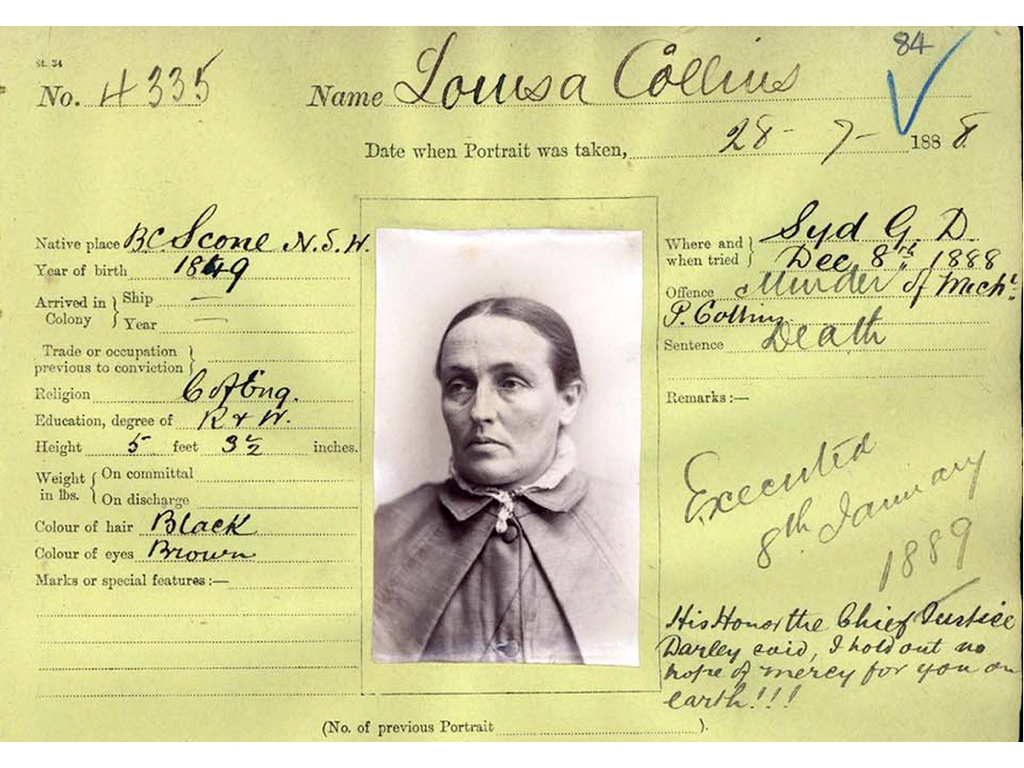

Louisa Collins, Darlinghurst Gaol Photographic Description Book, 1888. State Records NSW

The source of their fascination was Louisa Collins, who was convicted after four trials for the murder of her two husbands and sentenced to death by hanging. The journalist observed, horrified by the mob’s voyeurism, ‘it was repulsive to hear men and women…and mere boys and girls, quite children, wondering whether “she would kick much”’. Even the NSW Premier, Henry Parkes, proclaimed it ‘one of the most cruel, inexcusable, and frightful murders…in the world’s history’.

Inside the gaol walls, Louisa Collins walked calmly to the gallows and had no last words to share. Those who witnessed the execution of Collins described the ‘horrible’, ‘revolting’ and ‘disgusting’ scene that unfolded next. It was what one journalist termed, a ‘hideous bungling’ when the executioner pulled the lever…and nothing happened. When the executioner produced a mallet and hit it 4 or 5 times, the lever finally gave way, Louisa dropped. But onlookers watched horrified as the noose severed her windpipe. Louisa Collins was the last woman to be hanged in NSW.

It is poignant that I start tonight with Louisa Collins in this room of all rooms – The Cell Block Theatre was the women’s wing of Darlinghurst Gaol from 1841 to about 1909 and Louisa would have walked within these walls. She would have been experienced what it was like awaiting her fate in a facility built to hold 156, but would actually on occasion have over 400 female inmates alone. She was one of the 79 people executed at the gallows outside where we are gathered this evening.

But for many many years before these unfortunate souls met their end, this land was used by the Gadigal people, which is why I’d like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we gather tonight, and pay my respects to elders both past and present.

Good evening everyone, I’d like to thank Michele and everyone at the Environment and Planning Law Association for inviting me to speak to you tonight, it’s always an absolute pleasure to share the many interesting stories from this city’s past. And also to spread the word about the work of the Dictionary of Sydney – a wonderful online repository documenting the history of Sydney, with its urban myths, political players, writers, dreamers, its watershed moments and even…its social deviants, criminals and the certain undesirables of the community which we will explore tonight.

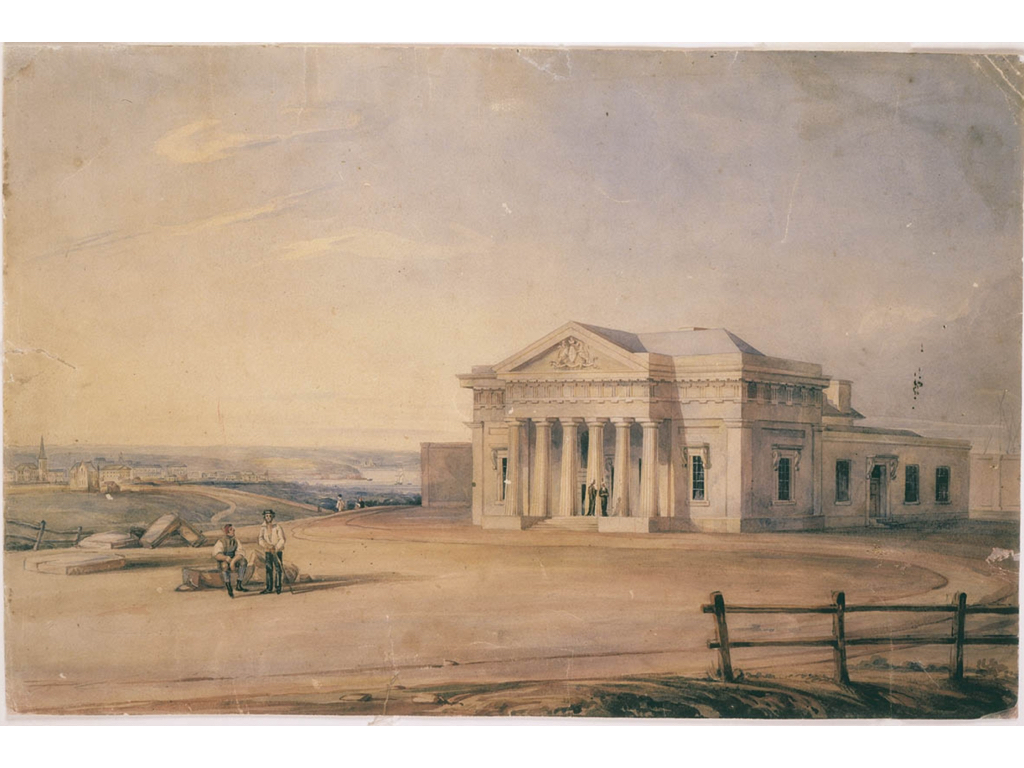

Darlinghurst Courthouse, c 1840. State Library of NSW

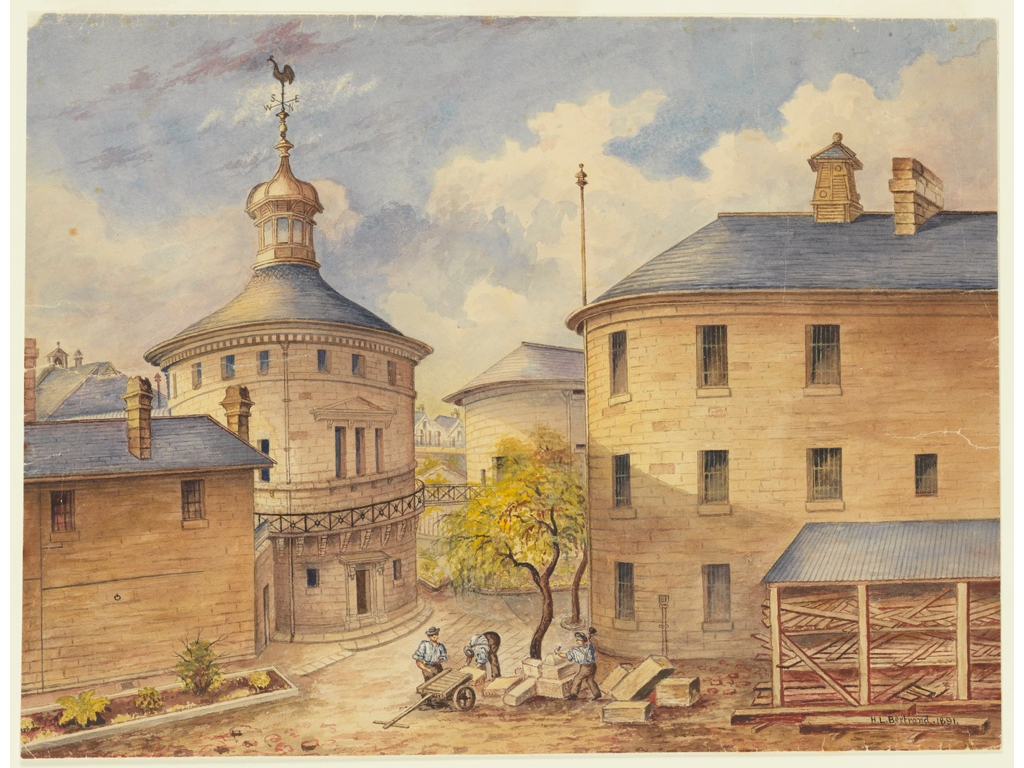

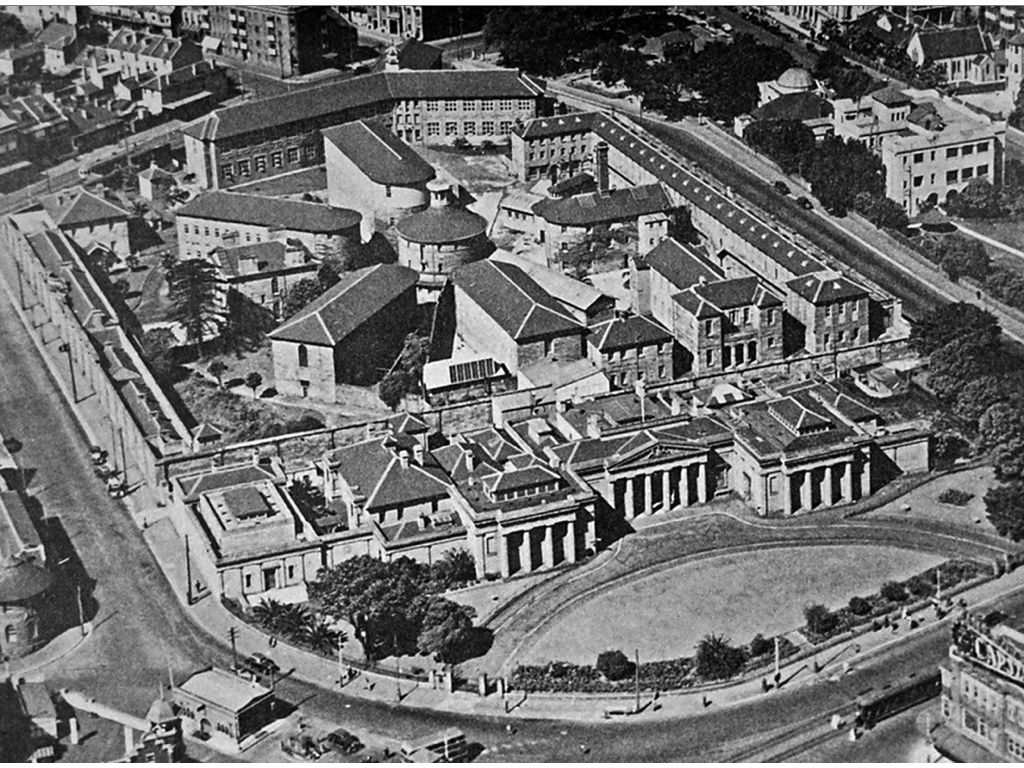

Darlinghurst Gaol – what a venue! I’m guessing some of you may have heard of its initial designer – the famous English-born architect who was actually transported to NSW for forgery, Francis Greenway. The objective was to design a building that would overlook Sydney and be on its fringes, as a constant reminder that the city was a convict town, and the elevated position of the area of Darlinghurst therefore provided the perfect prospect.

These walls, designed to confine convicts, were also constructed by convicts between 1822 and 1824. But with the initial flurry of activity and enthusiasm for the gaol’s construction, the funds waned and the facility remained empty for 12 years. Further funds were committed in 1835 when overcrowding in a gaol in the Rocks forced the government to act. It took another 50 years to complete the building with designs contributed by Mortimer Lewis and George Barney.

With its panopticon-style design, inmates were able to be watched through a centrally located structure in a move that was seen as progressive and for many, it symbolised a colonial ‘coming of age’. Yet despite this forward thinking and the fact that the gaol became Sydney’s main prison facility from 1841 to 1914, when inmates walked through its gates many of its buildings remained unfinished.

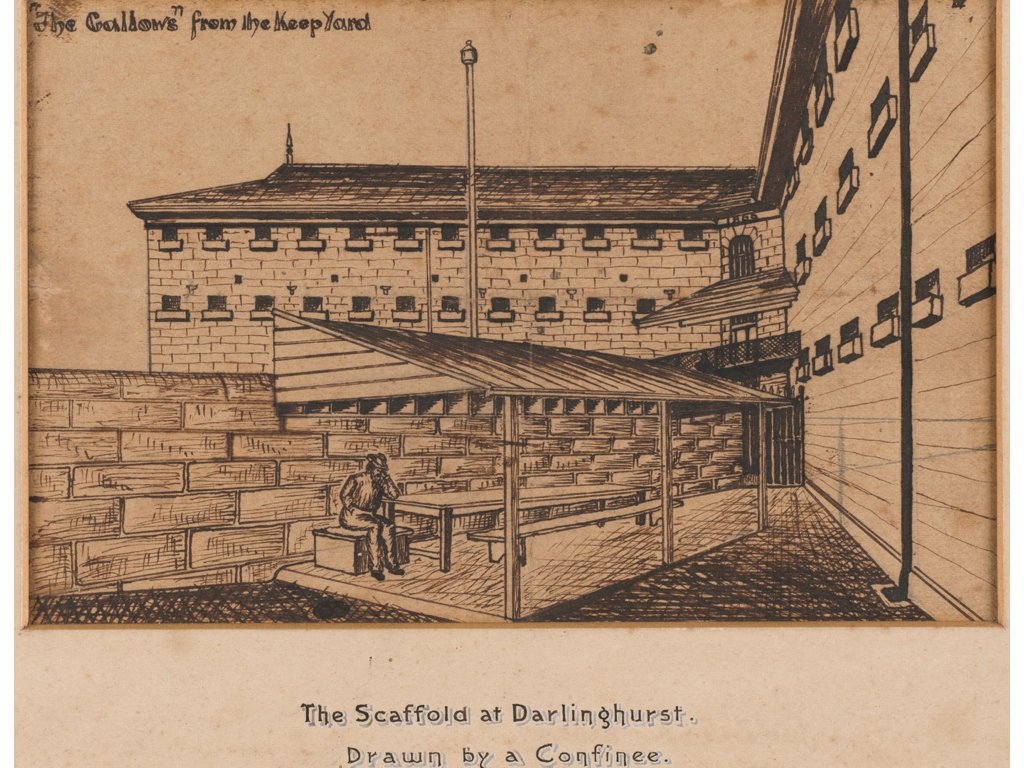

‘The Scaffold at Darlinghurst Drawn by a Confinee’. State Library of NSW

Among the gaol’s most famous inmates we find a range of fascinating stories; stories I think reflect the way the gaol operated and also society’s views on social deviance and punishment. The gaol saw its first public execution in 1844 when crowds gathered to witness the execution of John Knatchbull, a navy officer convicted of brutally murdering shopkeeper Ellen Jamieson with a tomahawk. There were makeshift gallows out on Forbes Street for the occasional macabre spectacle, in addition to the private gallows which were inside the main walls near the intersection of Darlinghurst Road and Burton Street.

Men, women and children swarmed around the gallows, and one journalist described how here and there, among those in the crowd you could hear ‘the heartless levity and unfeeling laugh of the unthinking, or the callous and reckless jeers of the hardened’. Onlookers described how Knatchbull struggled after the bolt was drawn and he dropped to his death, and afterward, his body remained hanging for all to see for an hour before it was cut down. His final confession written only days before read as follows, ‘I am guilty of the horrid deed for which I am to suffer death; and may the Lord have mercy on my soul’.

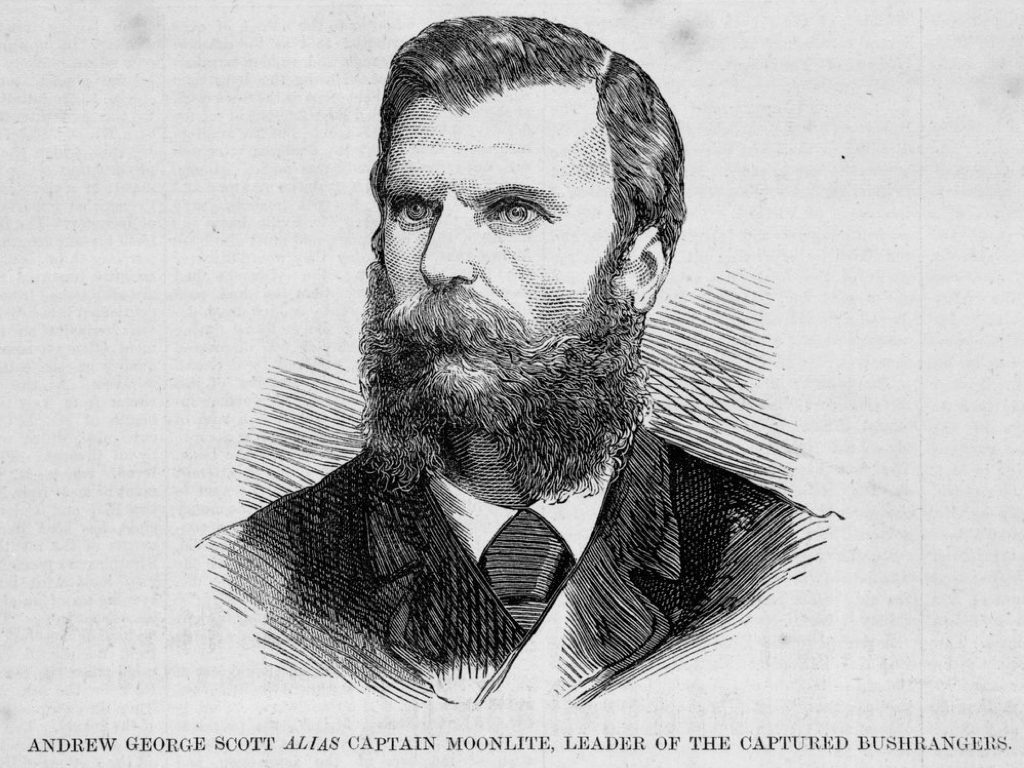

Andrew George Scott, alias Captain Moonlite, c 1879. State Library of Victoria

But to another famous inmate I want to turn your attention to. Andrew George Scott was born in Ireland and came to Sydney in 1867. Described as ‘dark, handsome, active and full of high spirits’, he was known for his impulsive acts of mischievous violence. There were many myths and legends that circulated about the man who became known as ‘Captain Moonlite’, bushranger and gang leader. Some say he served with Garibaldi in Italy, others said, though this is highly improbable, that he sent word to Ned Kelly asking to join forces when he was in Victoria in 1879. His first spot of notoriety came in 1869, when he disguised himself in a mask and cloak near Ballarat and robbed a bank. He fled to Sydney, and for some time was passing valueless cheques including one where he purchased a yacht but was arrested trying to sail to Fiji!

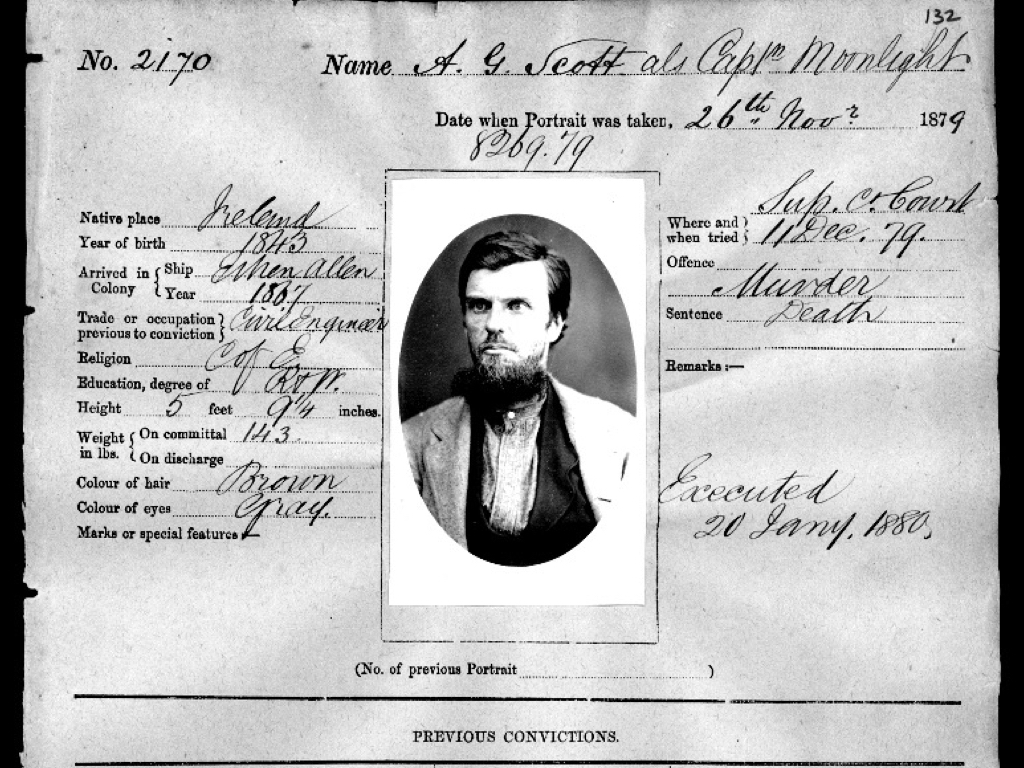

Captain Moonlite, Darlinghurst Gaol, 26 November 1879. State Records NSW

In December 1870, Scott spent time in Maitland Gaol and then in Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, feigning madness. In the late 1870s, he and his gang spent their time bailing up communities across NSW and proceeded to take prisoners, at one stage the gang had 25 prisoners. After he and one of his men were finally captured during a shootout with police at a sheep station, they were sent to Darlinghurst Gaol. While awaiting his execution, Scott wrote a series of letters which were discovered by historian and Dictionary of Sydney writer, Garry Wotherspoon. He was executed at 8am on 20 January 1880. According to one newspaper article, his name along with all those who had been executed at Darlinghurst Gaol was inscribed on the beam over the gallows, a ghastly record for those looking up in their last moments.

In a way, our next Darlinghurst inmate has become a far more famous outlaw than Captain Moonlite, who has been immortalised in Thomas Keneally’s 1972 novel, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, which was also turned into a film. Jimmy Governor was an Aboriginal tracker born near Dubbo in 1875. In December 1898, he married 16-year-old, Ethel Page, and they had a son together.

A dispute arose between Governor and his employer, the Mawbey family. Governor had heard his wife was being taunted by the Mawbeys and local schoolteacher, Helen Kerz, for marrying an Aboriginal man. With his friend Jacky Underwood, they confronted the women behind the taunts on the night of 20 July 1900. Jimmy alleged the women laughed at him, and Helen Kerz said: ‘…you black rubbish, you want shooting for marrying a white woman’. Losing control, the brothers armed with two nulla-nullas and a tomahawk killed the mother Grace Mawbey and Kerz as well as children Grace, Percival and Hilda Mawbey.

Darlinghurst Gaol from Burton Street, 1870. State Library of NSW

Though Underwood was captured, Jimmy Governor and his brother Joe proceeded on a 14-week rampage, terrorising a wide area of north-central NSW. Calling themselves bushrangers, they sought revenge on those who had wronged them, killing another four people. Joe was shot dead north of Singleton, and Jimmy was captured in October 1900. He was tried at Darlinghurst Courthouse and allegedly spent his final days in his death cell reading the Bible, blaming his wife and singing native songs. He was executed on 19 January 1901, reportedly taking one final draw of his cigarette and murmuring a prayer before the platform dropped.

Life could be difficult for inmates of Darlinghurst Gaol. George Barney’s designs were altered to accommodate more an more prisoners. Cells originally designed to house one inmate were holding three, and outside the walls near the entrance waste and sewerage collected in a huge pond, the stench rising up to greet anyone passing by on Old South Head Road. Imagine that!

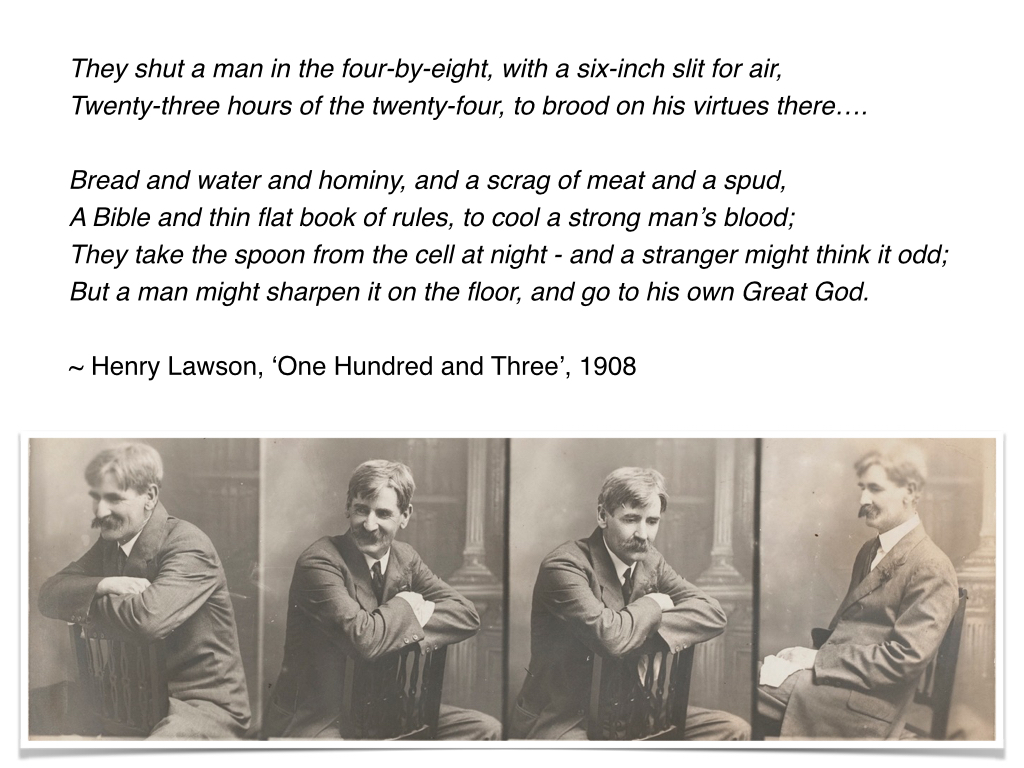

In 1905 the famous poet Henry Lawson called it a ‘barren hell’ when he served time for drunkenness and non-payment of alimony. And in true Lawson fashion, he wrote a poem about his experience in what he called, ‘Starvinghurst Gaol’, of which I will quote a few lines:

Excerpt from ‘One Hundred and Three’ by Henry Lawson, 1908. Image via State Library of NSW

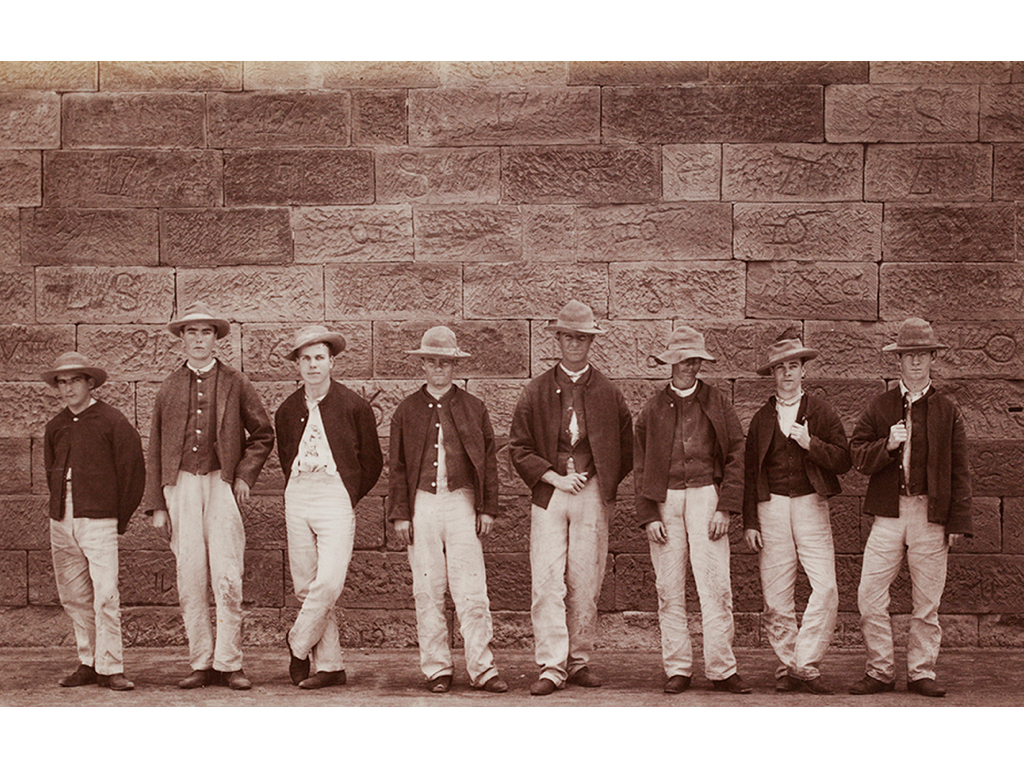

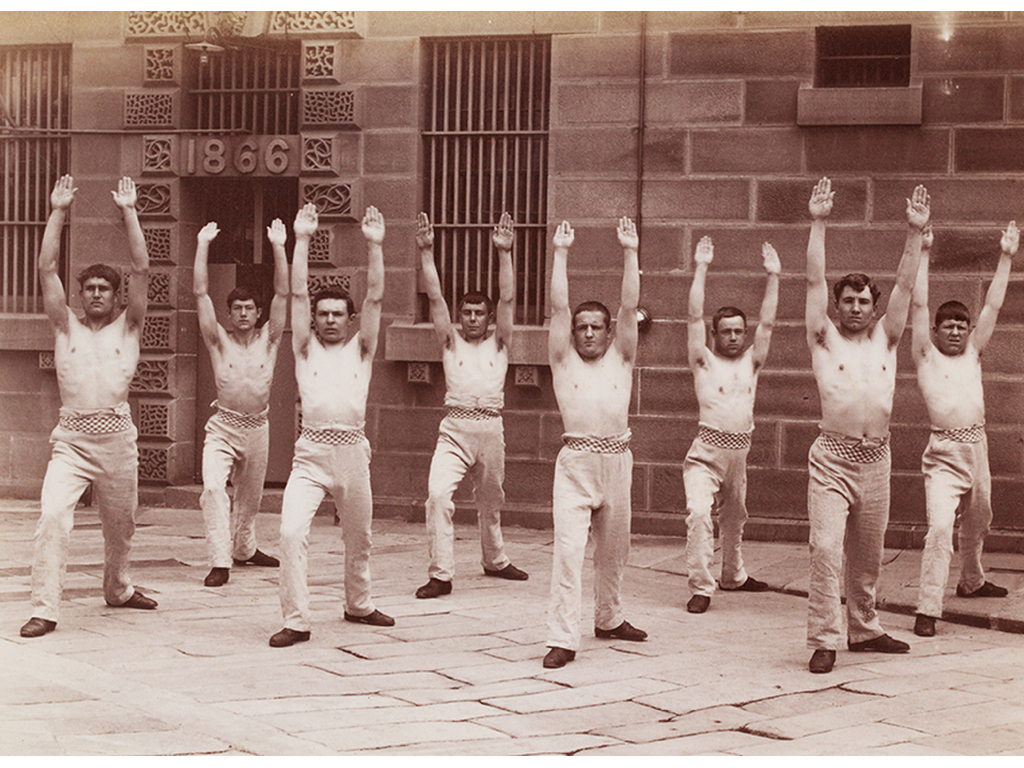

Prisoners in yard at Darlinghurst Gaol, 1884-86. State Library of NSW

But it wasn’t just the inmates that sealed the gaol’s reputation. The gaol’s first governor, Henry Keck, caused controversy during his eight-year reign with reports of rampant corruption. Keck and his warders were making money out of prisoners by releasing them from their cells to work on the outside. Men convicted of serious crimes including manslaughter, could be found working as coachmen and domestic servants! Prisoners were even let out in groups to go on picnics and fishing trips at Woolloomooloo, as long as they were back by nightfall. During his tenure as gaol governor, there were 25 escapes and a Committee of Inquiry called the gaol a ‘hotel’, and what was supposed to be what they termed a ‘house of mourning’ had turned into a ‘house of feasting’ and ‘luxury’. Despite the investigation, Keck was never punished for his corrupt dealings and left his job a very wealthy man indeed.

Darlinghurst Gaol, 1891. State Library of NSW

Here it is in 1891, a depiction somewhat reminiscent of a nice European village scene, though I would imagine not quite as rosy for its inmates! The reality was not quite so picturesque, and by the turn of the 20th century, the gaol at Darlinghurst was not longer at the city’s fringes like it was during the early 19th century – that old out of sight out of mind mentality. By the 1900s, as Sydney expanded the gaol formed part of the city’s heart, an awkward and constant reminder of the city’s darker side. So when a new gaol was built at Long Bay, the old Darlinghurst Gaol was finally closed in 1914.

After it served briefly as an internment camp during World War I, the buildings were converted into the East Sydney Technical College in 1921. Also that year, the National Art School took up residence in the old gaol buildings, offering diplomas in painting, sculpture, ceramics, design and commercial art. The place that was once the prison home of our most famous criminals, had become a cultural hub which saw the likes of Margaret Olley, John Coburn, Max Dupain, Reg Mombassa, Raynor Hoff and Wendy Sharpe forge their artistic genius and kickstart their careers.

East Sydney Technical College, 1936. National Art School Archives

In 1955, the award-winning American actress Katherine Hepburn visited the Cell Block we are sitting in tonight. She supported moves to turn this building into a theatre, making a speech saying how appropriate it was ‘that a member of the second oldest profession in the world should open a building which had housed women from the oldest profession’. Today, this venue continues to serve as a place for formal gatherings and as exhibition space for student works. At almost 200 years old, it is the oldest surviving large gaol complex in Australia.

And I can’t leave you tonight without putting a good word in for the Dictionary of Sydney. It is such a privilege to be a part of this extraordinary not-for-profit organisation. The Dictionary of Sydney documents in great detail Sydney’s vibrant past, its collection of essays, places, artefacts, multimedia including historical photographs and oral histories, provide a complex but engaging encyclopaedic resource for the community. This ever-expanding resource creates a richly contextualised history of the city, mapping it in space and time in a way that you can achieve so beautifully in the digital sphere. Over 300 authors have contributed their expertise and knowledge to the Dictionary, ranging from professors, to professional historians and local experts and enthusiasts.

The Dictionary of Sydney has been doing this work since 2004, and I hope you will all join me in the wish that it continue to do so. After all, even our most maligned citizens can reveal a little something of how this city was shaped, and how it came to be the city we all know and love today.

This talk was delivered on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney at the dinner for the Environment and Planning Law Association NSW annual conference on 16 October 2015.

Further reading

Dictionary of Sydney staff writer, Darlinghurst Gaol, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008

Darlinghurst Gaol posts, Scratching Sydney’s Surface