The second lady of the First Fleet voyage to Botany Bay in 1787–88, Lady Penrhyn, enters the annals of history as the slowest ship with the largest number of female convicts. Built in 1786, the 333-ton ship carried 101 female convicts, 20–35 crew, two lieutenants, two sergeants, three corporals, one drummer and 35 privates, under Master William Cropton Sever.1Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32

The women’s ship

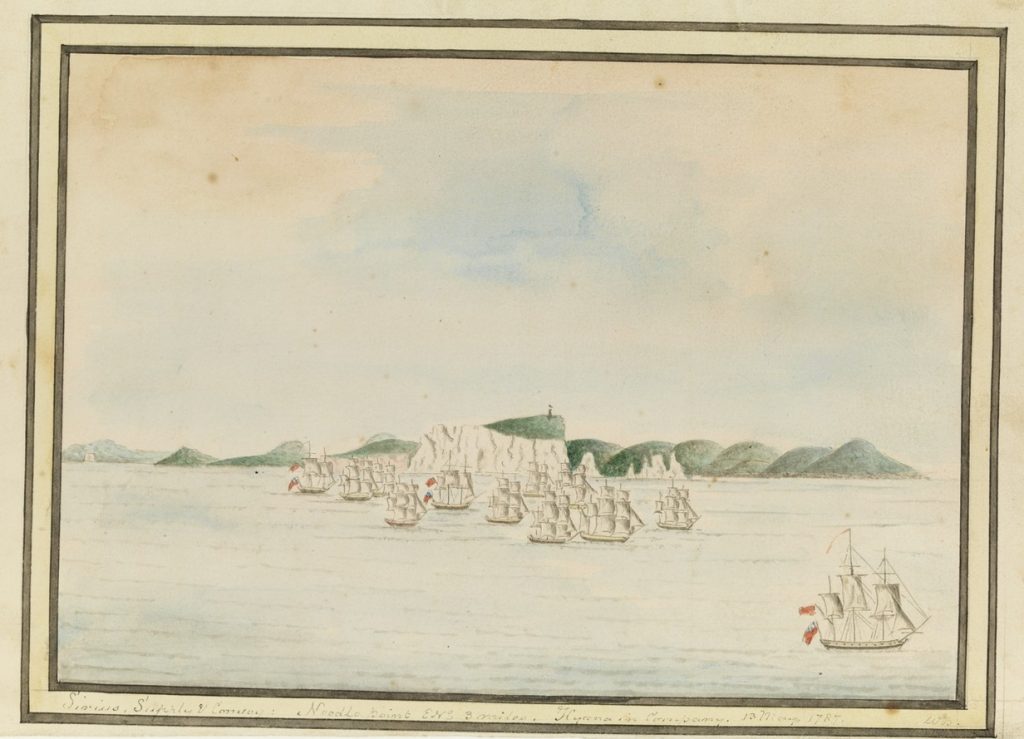

Sirius, Supply & Convoy: Needle Point ENE 3 miles, 13 May 1787, State Library of NSW

The Lady Penrhyn took on its first female convicts at Woolwich on 6 January 1787 and two days later, another 54 from Newgate Prison.2Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32 Arthur Phillip decided to segregate the female convicts from the men to protect those ‘who still retain some degree of virtue’.3’Phillip’s views on the conduct of the expedition and the treatment of convicts‘, 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales (Sydney: Charles Potter Government Printer, 1892), 51, viewed 10 January 2015 Despite this prostitution was rife and on 19 April 1787, Surgeon Arthur Bowes Smyth recorded five women were ‘put in irons’ after consorting with the crew.4Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015

Among the many convicts aboard Lady Penrhyn was 21-year-old prostitute Mary Allen, convicted of stealing from one of her clients, and her accomplice Tamasin Allen, described as a ‘lustyish woman with blonde hair’.5Don Chapman, 1788: The People of the First Fleet (Sydney: Cassell Australia, 1981), 27 Esther Abrahams, a Jewish milliner aged 15, was convicted of stealing and sentenced to seven years’ transportation. She embarked with her newborn daughter and developed a relationship with Lieutenant George Johnston on the voyage.6Don Chapman, 1788: The People of the First Fleet (Sydney: Cassell Australia, 1981), 23 Also on board were convicts Ann Inett, who would become the mistress of Lieutenant Philip Gidley King, Ann Yeates, who became the mistress of Judge Advocate David Collins, and Mary Branham, who became the mistress of Lieutenant Ralph Clark.7Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32 Shortly before the fleet set sail, Phillip observed their condition:

The situation in which the magistrates sent the women on board the Lady Penrhyn stamps them with infamy – tho’ almost naked, and so very filthy, that nothing but clothing them could have prevented them from perishing…there are many venereal complaints, that must be spread in spite of every precaution I may take hereafter…8Letter from Governor Phillip to Under Secretary Nepean, 18 March 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales (Sydney: Charles Potter Government Printer, 1892), 59, viewed 10 January 2015

The voyage

The Lady Penrhyn set sail on 13 May 1787, having completed food and water provisions the night before, however leaving without ‘a considerable part of the women’s cloathing’.9Letter from Governor Phillip to Under Secretary Nepean, 12 May 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales (Sydney: Charles Potter Government Printer, 1892), 104. Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 43; Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 At the port of Tenerife, Surgeon Smyth recorded Surgeon-General John White boarded on 5 June ‘to enquire into the state of the Sick’ and ‘pronounced the Lady P the most healthy Ship in the fleet’.10Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 5 June 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015

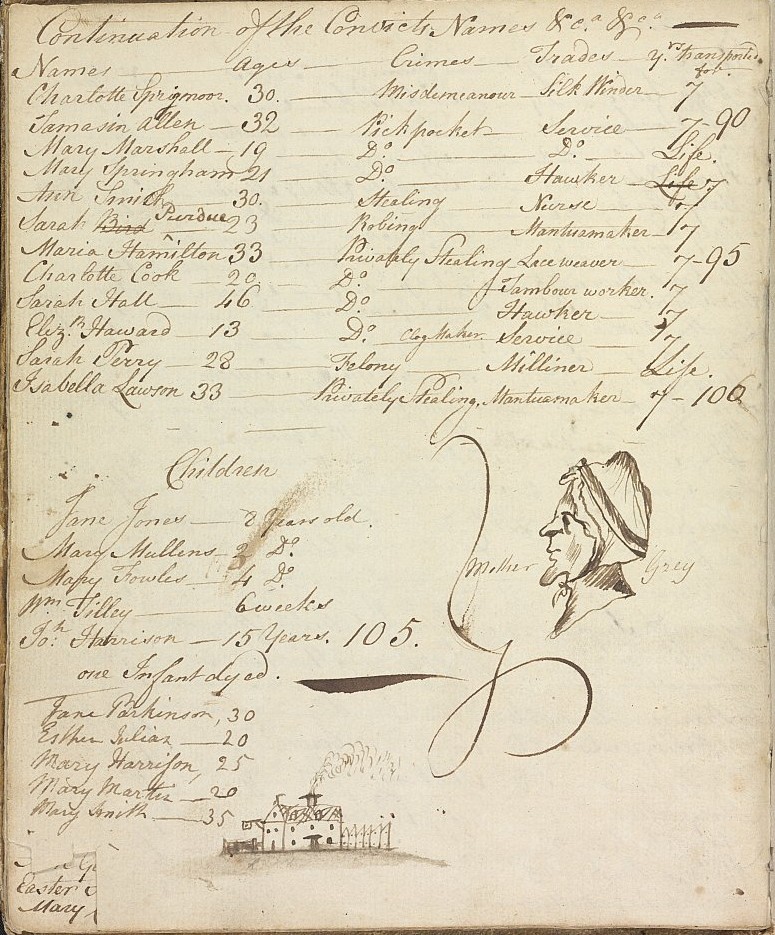

List of Female Convicts on board Lady Penrhyn, from the journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, May 1787, National Library of Australia

During the second leg, convict Elizabeth Beckford, 70, died of dropsy and ‘her corpse was committed to the deep’.11Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 11 July 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 As the fleet crossed the equator on 14 July, the women ‘fell ill with fevers’.12Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 14 July 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 Further troubles came in the form of dangerously low food supplies, so the signal from HMS Supply on 2 August at the sight of land must have been a welcome one for those on Lady Penrhyn who had just killed their last goose.

After a month at Rio de Janeiro, the fleet set sail on 4 September. The Lady Penrhyn made the slowest progress of all and 39 days later, the convoy arrived at the Cape. On the final leg to New South Wales, convict Jane Parkinson died on 18 November.13Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 18 November 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 By 3 December, Smyth recorded:

…we were ten thousand 5 hundred miles & upwards from England [and] have now 5 thousand 5 hundred miles to new Holland.14Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 3 December 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015

At this juncture Smyth recorded his opinions on the convicts. Their ‘punishment’ consisted of ‘thumb Screws’, ‘Iron fetters’ and in some cases, they were flogged ‘with a Cat of 9 tails’ and their heads shaved:

I believe few…were ever better, if so well provided for as these Convicts are…I believe I may venture to say there was never a more abandon’d set of wretches collected in one place…The greater part of them are so totally abandoned & callous’d to all sense of shame & even common decency that it frequently becomes indispensably necessary to inflict Corporal punishment upon them…15Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 10 December 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015

The arrival

As Lady Penrhyn rounded Van Diemen’s Land, Smyth had never seen ‘the Sea in such a rage’,

the Convict Women…were so terrified that most of them were down on their knees in prayers, & in less than one hour after it had abated, they were uttering the most horrid Oaths…that could proceed out of the mouths of such abandon’d Prostitutes…!16Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 10 January 1788, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015

They were about 520 miles from Botany Bay on 11 January, which was just as well as they had nothing to feed their livestock except ‘Sea bread’.

‘The Kangaroo’ 1787-89 by Arthur Bowes Smyth, State Library of NSW

On 20 January 1788, Lady Penrhyn anchored at Botany Bay. Whatever joy they may have felt was short-lived, as they were ordered to set sail again. With the ‘utmost difficulty & danger with many hairbredth escapes’ Lady Penrhyn entered Port Jackson on 26 January.17Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 26 January 1788, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 It was not until 6 February that the convict women disembarked; they had spent a total of 13 months confined to the transport. Smyth’s description of what happened next is one of the most famous, and indeed highly disputed, account:

At…abt. 6 O’Clock p.m. we had the long wish’d for pleasure of seeing the last of them leave the Ship — They were dress’d in general very clean…The Men Convicts got to them very soon after they landed, & it is beyond my abilities to give a just discription of the Scene of Debauchery & Riot that ensued during the night.18Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 6 February 1788, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015. See also Grace Karskens, The myth of Sydney’s foundational orgy, Dictionary of Sydney, 2011

The Lady Penrhyn departed Sydney Cove for China on 5 May 1788. Chartered by the East India Company to collect tea in China on the return voyage, the ship first called at Lord Howe Island for supplies before finally reaching its destination in October 1789. The Lady Penrhyn traded on the London-Jamaica route before being captured in 1811 in the West Indies and scuttled.

This article was originally published at the Dictionary of Sydney as part of their First Fleet series, supported by the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme.

References

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑7 | Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32 |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | ’Phillip’s views on the conduct of the expedition and the treatment of convicts‘, 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales (Sydney: Charles Potter Government Printer, 1892), 51, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑4 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑5 | Don Chapman, 1788: The People of the First Fleet (Sydney: Cassell Australia, 1981), 27 |

| ↑6 | Don Chapman, 1788: The People of the First Fleet (Sydney: Cassell Australia, 1981), 23 |

| ↑8 | Letter from Governor Phillip to Under Secretary Nepean, 18 March 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales (Sydney: Charles Potter Government Printer, 1892), 59, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑9 | Letter from Governor Phillip to Under Secretary Nepean, 12 May 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales (Sydney: Charles Potter Government Printer, 1892), 104. Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 43; Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑10 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 5 June 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑11 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 11 July 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑12 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 14 July 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑13 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 18 November 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑14 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 3 December 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑15 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 10 December 1787, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑16 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 10 January 1788, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑17 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 26 January 1788, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015 |

| ↑18 | Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China‘, 6 February 1788, transcript, viewed 10 January 2015. See also Grace Karskens, The myth of Sydney’s foundational orgy, Dictionary of Sydney, 2011 |