On 3 November 1927 scenes of ‘indescribable horror’ unfolded on Sydney Harbour. The Greycliffe ferry disaster became known as the city’s worst maritime tragedy and photographer Sam Hood was there to capture its devastating aftermath.

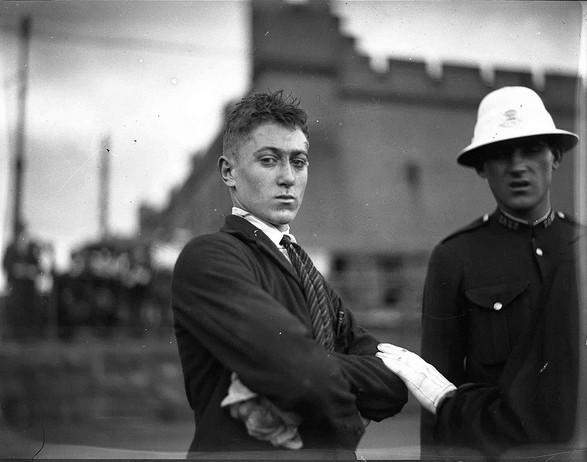

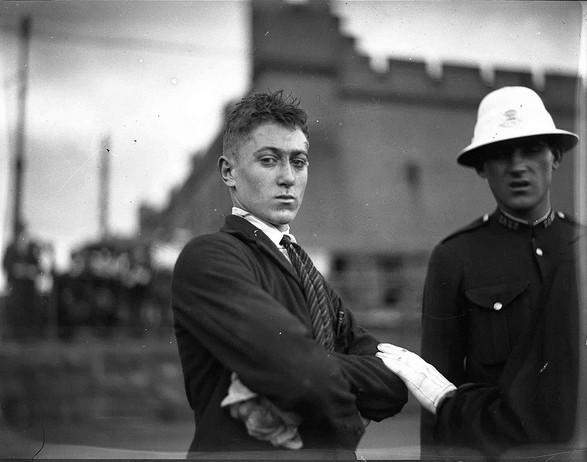

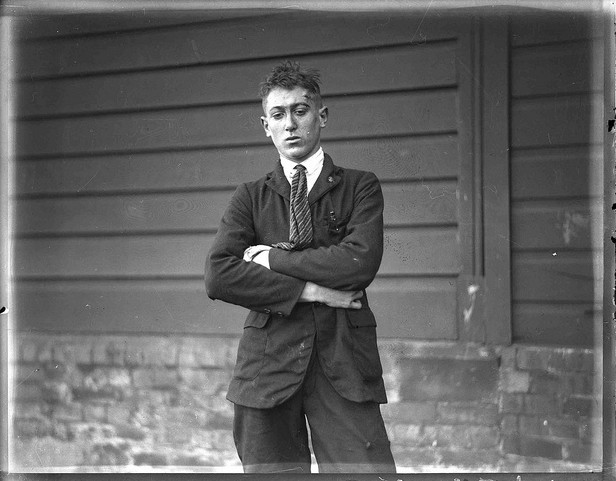

I stumbled across this curious photograph and the one word attached to the record for this image in the catalogue: Greycliffe. I knew this image was different. I was struck by his demeanour: crossing his arms not necessarily defiantly because I could see the injury to his forehead, the markings on his collar, piercing gaze directly into the camera, the gloved hand placed on his arm by a policeman. In the next one, he is pictured with a look that speaks to me of desolation, the injury seen more clearly.

[slideshow]

[/slideshow]And then I saw another one, others are out of focus and in the centre a man is carrying what is presumably an injured child. Yet another powerful image I knew I had to investigate further. But in order to understand this image, perhaps we need to rewind back to its inception…

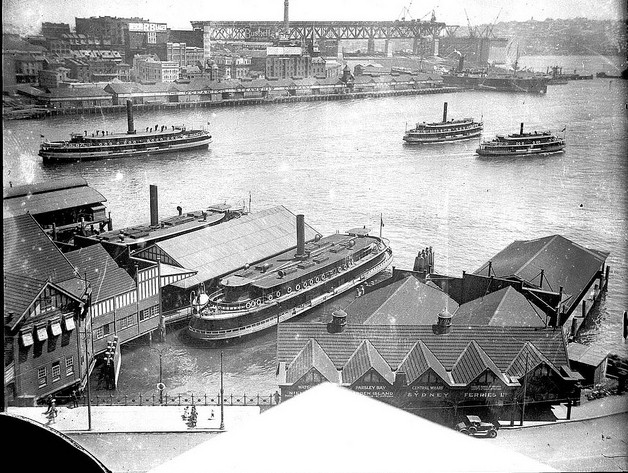

It’s a bright and sunny afternoon on Sydney’s bustling harbour, Thursday 3 of November 1927. We start at Circular Quay, with a backdrop of the new structure being built that would become one of the city’s key landmarks – the Sydney Harbour Bridge. On the Quay, the many jetties are full of incoming and outgoing Sydney ferries.

At Jetty number 1 Henry Storey described how he had caught a tram with a fellow school student to the Quay for the Watsons Bay ferry service. As they were seated aboard Greycliffe and slipped out of the wharf, a man rushed to the wharfside but was too late. He missed the ferry by seconds and stood there, ‘red-faced and angry’ as the ferry pulled away. Others were clearly not so lucky.

Henry noted that his friend, as a rule, sat in the Smokers Cabin of the ferry, in the end, the worst hit. But as he was about to enter, he ‘caught sight of a neighbour who was a ‘prize bore’, and he walked quickly on taking a seat on the outside.’ As the ferry steamed toward its destination, rounding Bennelong Point and the Fort Macquarie Tram Depot where the Sydney Opera House now stands, passing Garden Island making for Shark Island, Fred Jones was collecting fares in the Men’s Saloon. He glanced out the port-side windows and saw a large ship looming ahead barely 100 yards away, heading straight for the Greycliffe. Shouting to the men around him to get out, he ran to the engine room alerting his colleagues to the imminent danger.

What happened next has been described vividly in many newspaper reports of the day, differing slightly depending on what vessel the disaster was experienced from. However one image seems to stand out, and appears across many accounts.

Tahiti sliced through Greycliffe like a knife. In one report it notes the ‘sharp bow of the Tahiti bit into the ferry’. But I want to quote this particular report, it notes:

The actual impact was slight, and for several moments the ferry was carried through the water, turning slowly over until the keelplates were plainly visible. Then, like a huge knife, the bow of the Tahiti cut through the middle of the Greycliffe, shearing through the steelwork and wooden superstructure as though it were so much as a matchboard. A piercing shriek arose from the sinking ferry boat.

Drawing by John Allcot based on eye witness accounts, The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 November 1927, p 14.

Soon the shrieks of the ferry were joined by the screams of those aboard Greycliffe. ‘In a moment one half of the vessel had disappeared from view, and the other immediately became alive with scrambling terrified people.’ Those that occupied the lower compartments of the ferry struggled desperately, realising that unless they broke through the windows or gangway openings before the vessel sunk, they would drown.

Personal items and bits of timber littered the harbour as the scene of ‘unutterable desolation’ unfolded. As the ‘ghastly chorus’ of screams filled the air, one half of the vessel sunk into the murky depths within seconds, leaving a ‘swirling vortex’ behind with men, women and children struggling against the ‘suction created by the sinking ship’.

Greycliffe sunk within three minutes of impact.

For many on Tahiti, it was the piercing chorus of screams from the women and children that had alerted them to the collision in the first place. Many claimed they felt a ‘slight bump as the giant mail steamer crashed through the frail timbers of the ferry’. One passenger unwittingly told her friend ‘They are putting the brakes on’.

The open space in front of the Fort Macquarie Tram Depot at the Man o’ War steps, again where the Opera House now stands, was turned into a temporary casualty station. For nearly an hour, ambulance vehicles were travelling between the site and Sydney Hospital. Some victims were revived on the pathways at the steps; others were conveyed straight to the hospital with wounds of varying severity.

A trembling and bloodied John Corby staggered on to the temporary hospital station, uttering the following chilling words to reporters ‘Oh God, my poor wife and child. They have gone’. Corby had told of his plans to take his wife Mary and 6 year old daughter Noreen to Watsons Bay for the afternoon, when Greycliffe was violently struck. As he scrambled for lifebelts, he shouted to his wife to run down the gangway. The force of the collision threw him into the water. The next thing he knew he was on the surface of the water, surrounded by women and girls struggling to stay afloat. Noting that his wife could not swim, Corby finally collapsed as ambulance officers took him away from the media swarm. The following day, their bodies were found, they had been embracing each other when they drowned.

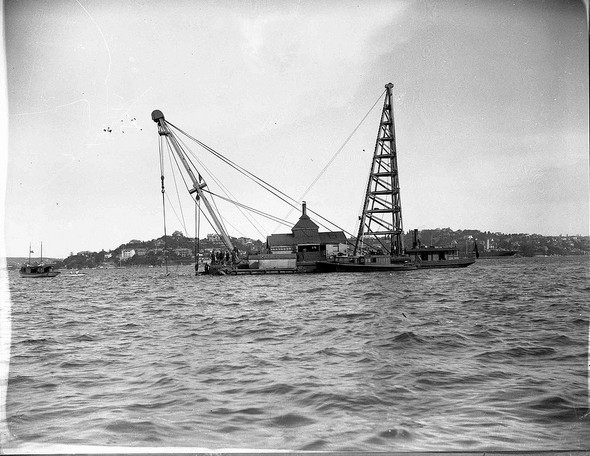

Sam Hood, the photographer behind these photographs, was at the scene to witness the chaos as it unfolded on the Man o’ War steps, and also the grisly task of recovering bodies trapped in the wreck off Bradleys Head. Harbour Trust divers Thomas Carr and William Harris worked in the days that followed to find the missing. On one occasion, Harris was tested when he found the body of 15 year old schoolgirl, Betty Sharp:

Just before finishing work on Friday, I decided to have a look around a portion of the wreck which had not hitherto been explored. You can imagine my feelings,when the figure of the little girl, standing upright, and with outstretched arms, loomed up before me. Her clothes were torn to shreds. Further investigation revealed that the little girl’s foot had become jammed between a mass of twisted steel rods…

Salvage workers from William Waugh Ltd of Balmain used a sheerleg crane to lift the vessel from the water. Hood captured these scenes and one of his photographs was published in Melbourne’s The Argus.

Thirteen bodies were recovered in the first day. The accounts from the divers remain some of the most harrowing. They seem to describe the victims as if they had been quietly floating and waiting in the depths, some of them with no obvious wounds, they had just been trapped. One man ‘had on a pair of spectacles, and near him floated the sodden remains of the afternoon paper he had been reading.’ Over the next few days, as the wreck was raised by the crane, more victims floated to the surface.

In all, 40 people lost their lives. The victims ranging in age from just 2 years old to 81 years old. A Greycliffe disaster relief fund was set up for the victims’ families and over the next few months, an inquiry and a coronial inquest was held to investigate their deaths. As Steve Brew mentions in his book Stolen Lives, the court findings were complicated and all conflicted. The Court of Marine Enquiry found Tahiti at fault, the Coronial Inquest found both vessels had been negligent, whereas the Admiralty Court found Greycliffe was to blame.

Both vessels appear to have altered their original course, however, there are other details that remain unresolved, such as the exact speed of both vessels when the collision occurred. With so many first-hand accounts and points of view it must have been a nightmare for investigators. Since then, no singularly accepted version of events or even how the incident occurred has been established.

Incidentally, only three years after the disaster, Tahiti sank southwest of the Tongan Islands with no loss of life.

So why was the Greycliffe/Tahiti collision so shocking for the people of Sydney? Perhaps, in addition to the high death toll, the fact that it remains, to this day, a mostly unsolved mystery. The many accounts of what happened that day throw the event into a dark uncertainty, and one that continues to fascinate us today.

But I also think the immediacy of the disaster, the fact that a terrible, unthinkable thing occurred right in the middle of a jostling city, a city that usually went about its business with little disruption, also adds to it. It brought the dreadfulness of human suffering to the fore; you couldn’t dismiss it as something that happened somewhere else and to someone else. That day, the city we all know and love mourned a grim reality played out on their beloved waterfront. Shockwaves permeated as the true horror unfolded revealing the many men, women and children who perished in the beautiful sparkling harbour.

I look at the terminology of the day contained in newspaper reports and first-hand accounts. Words such as unspeakable, horror, dreadful, tragedy, gloom and doom seem to pop out from the pages. And then I see Hood’s astounding black and white glass plate negatives from that day. They demonstrate not just the power of the image, but also that there are new stories being discovered, and fresh questions being raised. The historical puzzle becomes not so much more complicated, but more multi-faceted.

This seems to further prove to me, the continuing importance and relevance of history. Perhaps, in light of current discussions surrounding the place history holds in a contemporary context, now more than ever, the pursuit of the past holds exciting possibilities…and I believe we’re only scratching the surface.

NOTE: The above story is a combination of a talk delivered to the City of Sydney Historical Association on 12 July 2014 and a post published on the Australian National Maritime Museum blog on 19 October 2012. Reproduced courtesy of the ANMM.