Lord Howe Island was the exotic locale for an early Australian ‘talkie’, and the launching place for a disastrous voyage that claimed two of its actors. Nicole Cama drew on our Samuel J Hood Studio Collection, and records of the National Film and Sound Archive, to reconstruct the last voyage of the aptly named Mystery Star.

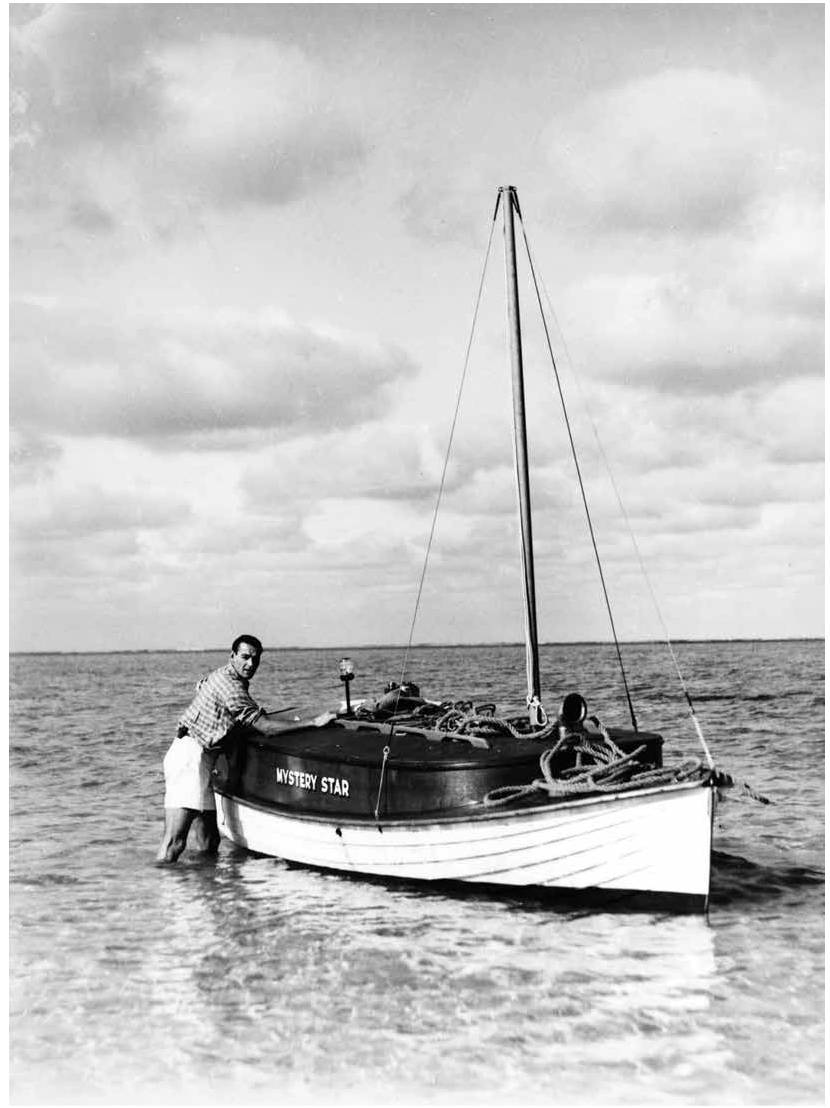

Brian Abbot standing at the stern of Mystery Star. Image courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

WHY DO THEY DO IT? Is it the promise of adrenaline-pumping adventure that draws sailors to defy the odds? Or is it the prospect of the finish line crowded with admirers eagerly awaiting their arrival that spurs them on? Perhaps it is the attraction of the unknown, or an irresistible desire to explore a deep blue expanse that promises all manner of peril to those brave enough to sail across it.

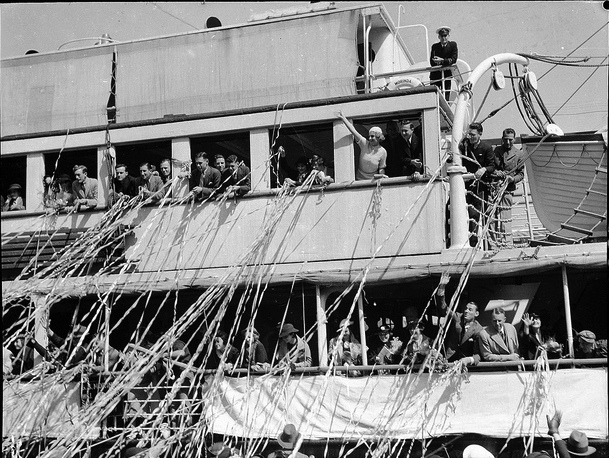

On 5 September 1936, crowds gathered at Wharf 10 in Walsh Bay, Sydney, to farewell the cast and crew of a new Australian ‘talkie’, Mystery Island. Among those about to board the Burns Philp liner SS Morinda was actor Brian Abbot (real name George Rikard Bell), who was recorded by commercial photographer Samuel J Hood farewelling his wife, Grace Rikard Bell. In his photo, in the museum’s collection, they happily embrace, completely unaware that this would be the last time they would see each other. Over a month after this photograph was taken, Brian Abbot and fellow castmate Desmond Hay (real name Leslie Hay Simpson) set off to cross the ‘stormy Tasman’ from Lord Howe Island back to Sydney – and were never seen again.

For months preceding Morinda’s departure, newspapers had reported that the flm would be shot in an exotic South Sea location. The all-Australian cast and crew were to sail to Lord Howe to work on the Commonwealth Film Laboratories’ first feature-length film with sound. Articles also profiled the film’s leading lady, Jean Laidley (real name Jean Angela Laidley Mort), great-granddaughter of Thomas Sutcliffe Mort, industrialist and founder of Mort’s Dock in the Sydney harbourside suburb of Balmain. Laidley was tall, slim and golden haired, with a movie-star air that matched Abbot’s dashing good looks. Sam Hood captured the excitement and glamour of the emerging sound-film industry in photographing the cast. Laidley was Audrey Challoner, the archetypal beautiful damsel in distress, and Abbot was the handsome hero, Morris Carthew. As they waved goodbye that day, while streamers were thrown over the side of Morinda, it is easy to imagine that the passengers were eagerly anticipating the next few weeks.

Reports trickled back home of life filming on the island. In one story, Laidley’s ‘fortitude’ was tested as she picked up a bird which ‘proved so wild that it pecked her arm and hand severely’. Another dramatic report described how one evening, after filming on the Admiralty Group of islets, the cast and crew had been unable to return to their base on Lord Howe as the seas were too rough. The filming was fraught with other complications due to variable weather. It rained six days a week on average, poor electricity meant make-up had to be applied by candlelight and the sound crew were constantly plagued by noise interference from the crashing waves.

The most fascinating and mysterious parts of this story are an article published in The Australian Women’s Weekly on 24 October 1936 and the events that unfolded after filming wrapped. Brian Abbot wrote a letter to the magazine that contained these ominous sentences:

I shall be attempting a very dangerous voyage in October … However, I have strong personal reasons for no word of this trip of mine to be published until it has actually begun.

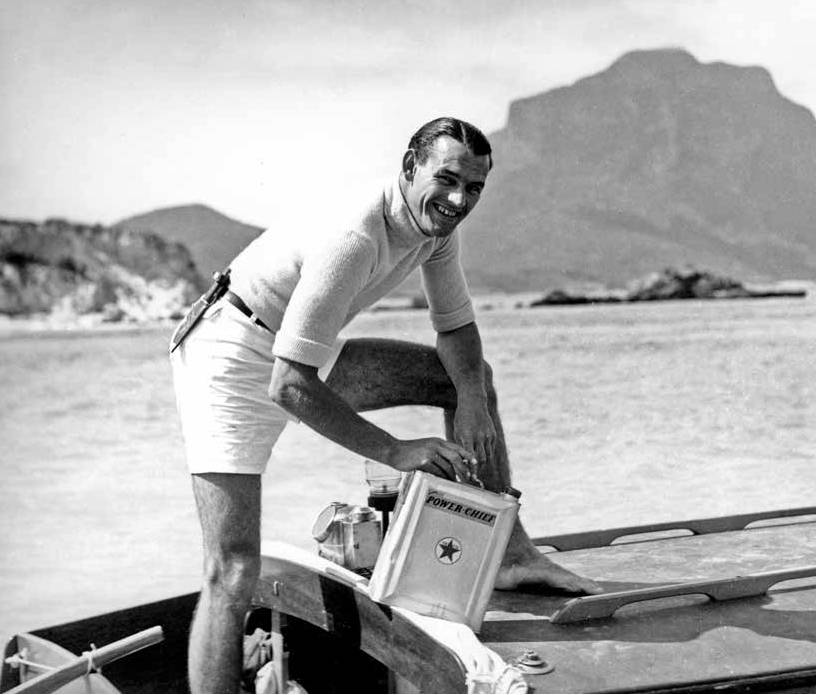

Brian Abbot and his motor launch Mystery Star in Lord Howe Island lagoon. Image courtesy National Film and Sound Archive.

No hint was given as to why the trip should be shrouded in secrecy; nor is much known of why Brian Abbot chose to attempt such a risky venture. The film’s producer, George D Malcolm, claimed that the voyage was undertaken as an ‘adventure’. Despite Abbot’s dramatic words, it is clear that the voyage was not decided on a whim. Abbot had taken his motor launch, Mystery Star, from Sydney to Lord Howe, reportedly with a view to making the 725-kilometre return trip in that vessel rather than Morinda. Whatever Abbot and Hay’s reasons were, however, newspaper reports and witness statements appear unanimous about one crucial detail – that the two men were ill equipped and unprepared for rough conditions.

On 6 October 1936, as Morinda returned to Sydney, Abbot and Hay were still on Lord Howe Island preparing for their dangerous voyage. Abbot posed for publicity shots under the bright sky pretending to sail away while waving to a crowd of onlookers. Hay is noticeably absent from the photographs. At 10.15 pm, however, the real journey commenced. The pair set off in the 16-foot (4.88-metre) launch, reportedly equipped with a two-and-a-half-horsepower engine, 40 gallons (180 litres) of water, two cooked legs of mutton, biscuits and chocolate. Abbot claimed they would reach Sydney in six to eight days. As the eighth day came and went with no sign of the two actors, concerns for their safety trickled through the press.

At least two newspapers noted that these ‘grave fears’ were being eased by the ‘definite information’ that the launch was ‘unsinkable’. This claim was outweighed by most reports, which focused on the precarious nature of the adventure and on information that the two men were relying almost completely on the engine. In a bid for self-preservation as much as to reassure ‘anxious relatives’, Mr G Chapman of Chapman and Sherack, the Sydney company that manufactured the engine for the launch, told the press that the vessel had been fitted with two buoyancy tanks, which would ensure that the vessel would ‘float with a foot [30 centimetres] of freeboard even when completely swamped’. A ‘waterproof canvas apron’ had also been designed to securely cover the opening of the cockpit. Chapman said that Abbot had previously visited their factory to understand how their engines were made and even took a test trip on the ocean off the coast of Sydney in a craft similar to Mystery Star. According to Chapman, ‘the only possible source of danger which could be foreseen … was that the boat might take a large quantity of water aboard, and that the magneto might be put out of action’.

Despite Chapman’s assurances, anxiety began to dominate reports of the ‘hazardous voyage’, and damning questions were raised concerning the pair’s preparedness for such a journey. By noon on 14 October, the craft was declared overdue and an aerial search commenced. Over the next fve days, three aeroplanes covered the area off the east coast of Australia. In the meantime, requests for assistance were made by the two men’s relatives, including Grace Rikard Bell and Desmond Hay’s mother, brother and sister. They appealed to the minister for defence, Sir Archdale Parkhill, to aid in the rescue of their loved ones through the use of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). In addition, Captain Norman G Roskruge, deputy director of navigation and lighthouses, requested that all coastal stations and vessels keep a look out for the ‘missing mariners’. Eventually, the Royal Australian Navy’s HMAS Waterhen was tasked with searching the enormous stretch of sea between Lord Howe and Sydney by both day and night. The Richmond (Sydney) squadron of the RAAF also pledged assistance.

A last farewell: Brian Abbot and his wife Grace Rikard Bell on board SS Morinda before its departure from Sydney. This photograph was also published on page 2 of The Australian Women’s Weekly on 24 October 1936. Samuel J Hood Studio, ANMM Collection.

As is usual in such grave cases as these, contradictory reports were published and various ‘experts’ were quoted at length in the media. The pilot conducting an aerial search, Ernest Collibee, claimed that the men had only carried sufficient petrol and food for 10 days. A certain ‘Sydney motor boat proprietor’ told The Sydney Morning Herald that the engine would run for approximately five hours per gallon (4.5 litres) of petrol, that the launch would reach speeds of up to two knots, unless it was assisted by favourable winds, and that it would take nine days to reach Sydney.

To curb the rumours, Hay’s relatives had sent a wire message to Lord Howe to confirm the details. Alarmingly, contrary to early reports and according to those who saw the adventurers depart, Abbot and Hay left with a compass as their only piece of navigational equipment, plus food provisions for 10 days, 12 gallons (55 litres) of water and 48 gallons (218 litres) of petrol. They also had a complete spare engine, shafting, a propeller, a small leg-of-mutton sail, one paddle and a sea anchor. They estimated that the petrol would last for eight and a half days. Others said that amount of petrol would last 10 days.

Added to the realisation that the provisions and equipment were insufficient were constant morbid weather updates. Though the voyage started out in clear conditions with a moderate north-west wind, the next day saw the wind increase and the seas roughen. By day two, the wind was described as a ‘half a gale from the northwest’, which may have put the craft in danger of capsize. On day three, a strong southerly developed, which may have created heavy swells. The crew of Waterhen had to use lifelines to move around on deck and stated that the launch would have had ‘no chance’ in those same conditions. Faced with discouraging reports from the rescue teams, Hay’s relatives pinned their hopes on the possibility that the vessel had been swept southward, beyond the area patrolled. Grace Rikard Bell ‘would not dream of giving up hope’ and Abbot’s father added, ‘seafaring men have told me … that sometimes a small boat can come through much better than a larger one’. On 22 October, the search comprising Waterhen and the RAAF – which had allegedly cost more than £1000, or the equivalent of about $86,000 today – was abandoned.

During the days that followed, details came to light which make their story all the more intriguing. On 19 October, Jean Laidley was quoted as saying that the skiff was so small that she declined to sail in it during filming, even to a small island near Lord Howe. Another tragic detail was relayed by Chapman, who said that when the waterproof canvas cover was designed, only one opening had been provided and it had been Abbot’s intention to make the voyage alone. On 27 October, a Mr R Alott of Sydney, who witnessed the pair sailing from Lord Howe, claimed:

Abbot seemed satisfied that he would complete the journey … [Hay] did not seem so sure. Most of the islanders seemed to think that it was a foolhardy idea. The Mystery Star looked a little cockle shell. There seemed to be only about nine inches [23 centimetres] of freeboard at the stern when it was fully loaded. Nearly everyone present when it departed advised the two men against the trip, but Abbot decided to set out. (‘Missing skiff’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 October 1936, page 11)

Production shot of cast and crew on Lord Howe Island: Jean Laidley (starring as Audrey Challoner), Desmond Hay (starring as Packer), George Malcolm (producer) with hands on head, and Jack Bruce (production supervisor) with earphones on. Image courtesy National Film and Sound Archive.

If only Abbot and Hay had heeded those warnings. Abbot’s stubborn insistence to press on is particularly poignant when one considers that this was not, in fact, his first dangerous undertaking. His father had stated he had ‘implicit faith in his son’s resource in the face of danger … in addition to having experience at sea’, Abbot was ‘a keen yachtsman, and was seldom without a boat of some description’. As a young boy, he allegedly ran away from school and hid in a cave at Ben Buckler in Bondi, Sydney, where he existed on sardines and condensed milk. Finding that this was more than he could handle he eventually returned to school, but left for good at the age of 15 to take a job as a jackaroo in Queensland before discovering his ‘love of the sea’.

Abbot’s adventures earned the newspaper headline ‘Hazardous voyage’ no less than three times: in the Kalgoorlie Miner on 9 October 1936, in connection to the Mystery Star trip, and, five years before, in The Sydney Morning Herald on both 2 September and 13 October 1931. That earlier voyage was attempted by Abbot, under his original name George Rikard Bell, and Charles Boswarva in a 16-foot (4.88-metre) canvas canoe named Ker-wee-ah. On 25 May 1931, they departed Indooroopilly in Brisbane, Queensland, in an attempt to paddle the 700 miles (1,127 kilometres) up the coast to Rockhampton ‘to win a small bet’. The canoe, which was barely 2 feet 8 inches (80 centimetres) wide, encountered rough seas and ‘persistent sharks’. The vessel capsized near Coolum Beach on the Sunshine Coast and most of their gear was lost. George (not yet known as Brian Abbot) spent a month in Gympie Hospital with a poisoned leg, having injured it scrambling over sharp rocks as they swam ashore to safety. By this point, the canoe had 22 patches, but the pair continued northward on 23 August.

They were forced to make their way on foot for the last seven days of their journey, as the canoe had been smashed beyond repair. They had gone without drinking water for three days before they arrived in Rockhampton on 18 October 1931.

Mystery Island cast and crew Brian Abbot, Jean Laidley, George D Malcolm (producer), George Doran (actor). Samuel J Hood Studio, ANMM Collection.

After the canoe trip, George Rikard Bell worked on TSS Kanowna and SS Christina Frazer, then began pursuing a career in acting under the name Brian Abbot. The Sydney Morning Herald concluded on 14 July 1936, ‘As Mr Abbot didn’t believe in setting for the third time to prove that fate was against him, he promptly decided that there were other adventurous jobs to be had which didn’t carry the risk of drowning’. Ironically, this article appeared three months before Abbot set sail for the last time.

For all Abbot’s ‘iron nerve, uncanny endurance, and unfailing resource’, he ignored a detail that seemed so glaringly obvious to all else on the island but him: that to sail Mystery Star across the Tasman was tantamount to suicide. Yet he was a man ‘born with a thirst for adventure’ and his overpowering inclination to tempt fate was, and continues to be, shared by many. Just two weeks after Abbot and Hay set off, Gower Chase Wilson, a resident of Lord Howe Island, set off with his son Jack and three others on the same voyage in reverse, on board the 32-foot (9.75-metre) launch Viking. They met the same fate.

We will probably never know exactly what happened during Abbot and Hay’s journey. Based on the newspaper reports, statements from those present, and what we know of an area notorious for its ferocious conditions, we can form an idea of what they may have faced. ANMM curator David Payne believes that despite the enclosed cabin the craft could have been overturned in rough conditions and then swamped. Although an experienced sailor, Payne stated that he would be wary of taking the launch even into close offshore waters. The northern part of the Tasman, where Abbot and Hay would have been, may be less wild then the southernmost areas, but it is just as changeable. Calmer conditions can be interrupted, quite dramatically, by the convergence of weather patterns that create savage storms, winds up to 60 knots and swells that can reach up to 10 metres. Coupled with the fact that the pair were ‘not skilled navigators’, this would have made a deadly combination.

The flm cast and crew leaves Sydney for Lord Howe by SS Morinda; leading lady Jean Laidley (in white) waves at the top right, and ill-fated actor Brian Abbott waves from the deck below her. Samuel J Hood Studio, ANMM Collection.

It’s as if Brian Abbot the actor, still in character as Morris Carthew the hero, had decided that this was his chance to prove himself and achieve the impossible; or that Carthew had materialised in the form of Abbot, with no trace left of the foolhardy young George Rikard Bell, who almost drowned attempting to paddle up the Queensland coast. That had been five years earlier. This voyage was so much more. There is an eerie parallel between Abbot and Hay’s voyage and the plot of Mystery Island, which concerns the survivors of a shipwreck – among them a detective and a killer – stranded on a deserted island. Except Mystery Island was make-believe and Mystery Star cost them their lives. In a way, the film morphed into a nightmarish reality. As Abbot eerily articulated in his letter to the Women’s Weekly:

In our own ways each of us has become a part of this, our own ‘Mystery Island,’ and our work to date has already shown that … [w]e don’t need to imagine ourselves in our parts on an imaginary island; we live the characters we play, and ‘Mystery Island’ IS ‘Mystery Island.’ (The Australian Women’s Weekly, 24 October 1936, page 37)

In a case of life imitating art, they paid the ultimate price. Their voyage remains a sharp reminder of what can go horribly wrong in the pursuit of adventure.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Simon Drake and the Access team at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia in researching this story. Excerpts of Mystery Island appear on the NFSA Australian Screen portal.

NOTE: This story was originally published in Signals magazine, Issue 104, Sep-Nov 2013, pp 30-37. Reproduced courtesy of the Australian National Maritime Museum.