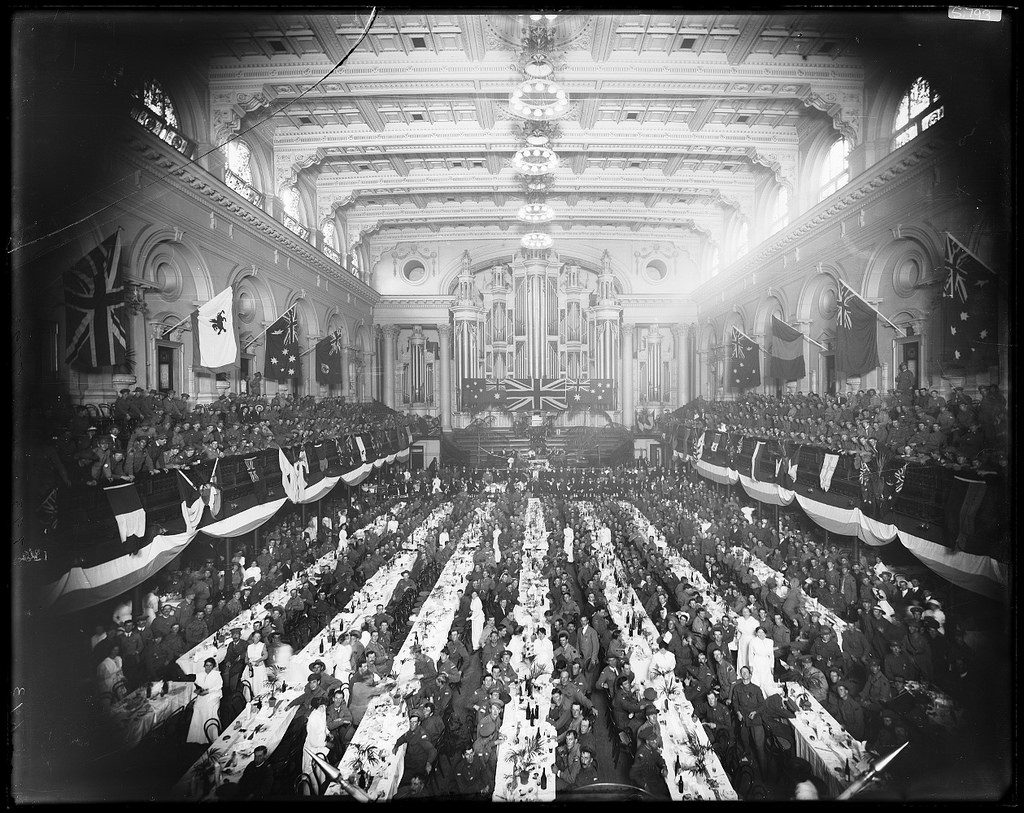

ANZAC Day 1916 dinner for returned soldiers, Town Hall, Sydney. State Records NSW

This Saturday will mark 100 years since Australian troops landed at the Gallipoli peninsula and commenced a disastrous eight-month military campaign. Every 25 of April we remember that first day of battle, but how did these commemorations begin? I spoke to Mitch on 2SER Breakfast about it this morning.

Neil Radford, Dictionary of Sydney volunteer and contributor, notes the Gallipoli campaign was the first major military action fought by Australian and New Zealand forces during World War I. He notes the earliest use of the term and concept ‘Anzac Day’ probably occurred in Adelaide in October 1915, when the South Australian Government announced a ‘patriotic procession and carnival’. Many of these processions were designed to raise funds to provide home comforts for the soldiers at the front. But the Mayor of Brisbane proposed that his state, and the other states, designate a particular day of solemn observance.

At the same time, Sydney City Council began discussing the commemoration of the first anniversary of Anzac in February 1916. At a council meeting, the Lord Mayor said that ‘the imperishable glory achieved at Anzac had opened a new page in Australian history’. By March, the NSW premier announced the government supported the idea of a national commemoration which included church services and a minute’s silence, and he wanted to see the day devoted to fundraising for a memorial and to recruiting. The Returned Soldiers Association enthusiastically assumed the responsibility of organising the event. But not all responded in support of the day, with some claiming the money could be better spent on supporting wounded soldiers and bereaved families.

Wreaths on the Cenotaph, Martin Place, Sydney, Anzac Day, 25 April 1930, Sam Hood. State Library of NSW.

Despite these concerns, Sydney’s first Anzac Day went ahead on 25 April 1916. At 9am every train and tram was brought to a standstill ‘in order that the passengers may give three cheers for the King, the Empire, and the Anzacs’. At 10am, 5,000 returned soldiers paraded through the city and at 11:30am until 2pm, all government offices and many businesses closed to enable staff to attend a commemoration service in the Domain. At midday, a minute’s silence was declared, and the Lord Mayor later entertained troops at a luncheon. Recruitment campaigns proliferated throughout the city and suburbs, a commemoration concert was held in the Sydney Town Hall in the evening, and more than £5,000 was raised for a memorial in the city.

For the duration of the war, Anzac Days followed suit. The parade was cancelled in 1919 as the influenza epidemic prevented people from assembling in large numbers. The following year the 25 of April was declared a national holiday, and in 1929, when the Martin Place Cenotaph was unveiled, the ceremonies moved to the city. During the 1920s, many returned servicemen decided to gather together informally and privately as a way to keep in contact with each other and remember those who did not come home.

As time passed, however, the Anzac Day parade and its commemorative services have formed an entrenched tradition. And, as we now know, this concept of Anzac Day as a turning point in Australia’s history was something that began quite early on in the piece, and indeed it continues to characterise conversations about the war to this day.

Check out Neil Radford’s original article at the Dictionary of Sydney and listen to my segment at 2SER radio. For other interesting segments, see my Dictionary of Sydney project post and visit the Dictionary of Sydney blog.