Much has been written about the idea that Gallipoli heralded a new phase for Australia’s identity; about its symbolism and status as a historical turning point. Whatever the validity of this idea, at the core of it is a powerful notion of the ‘Anzac spirit’ – a potent image and an entrenched belief which continues to characterise commemorations to this day. During the war, a number of business owners recognised the power of this concept and exploited it for commercial purposes. Even with the introduction of legislation which prohibited use of the word ‘Anzac’, these businesses appropriated the idea of the Anzac soldier to create a sense that their products and brand somehow possessed the same qualities intrinsic to these men.1See Jo Hawkins, ‘Anzac for Sale: Consumer Culture, Regulation and the Shaping of a Legend 1915–21’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2015, pp. 7-26.

The symbolic power of Anzac was something that was recognised not long after the commencement of the very ill-fated campaign which inspired its conception. In an article that would become known as one of the first to present the notion of the ‘Anzac spirit’, British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett proclaimed the Australians ‘rose to the occasion’ at Gallipoli’s shores.2’Australians at Dardanelles: Thrilling Deeds of Heroism’, 8 May 1915, The Argus, p. 19 It had been 11 days since the troops landed at Anzac Cove and it was the first report to be published for Australian readers, eagerly anticipating news from the front. In another article, the ‘special correspondent’ noted Australian troops ‘had behaved with that splendid courage, that splendid fearlessness’ and had ‘faced death with a cheer’.3‘Battle of Gabe Tepe’, 23 June 1915, The Age, p. 13 Furthering these notions, official war historian Charles W Bean wrote extensively about the Gallipoli campaign and later of how Anzac represented ‘reckless valour in a good cause…enterprise, resourcefulness, fidelity, comradeship, and endurance that will never own defeat’.4Charles W Bean, Anzac to Amiens, (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1983), p. 181 Prime Minister William M Hughes spoke to Australian troops a year after the Anzac Cove landing saying the day signalled ‘the imagination of a new era’ and prophetically announced ‘Whatever may happen in the future Anzac Day will remain one of the greatest in Australian history, and on every anniversary will be told the story of a blood baptism’.5‘Australia’s Great Day’, 25 April 1917, The Advertiser, p. 7

In addition to messages about the Anzac character and bravery at Gallipoli, there also existed a sense that this very idea was beyond all materiality, that it would somehow come under threat and need to be protected. In his speech, Hughes stated: ‘Into a world saturated by material things…which has made wealth the standard of greatness, comes the sweet purifying breath of self-sacrifice’.6‘Australia’s Great Day’, 25 April 1917, The Advertiser, p. 7 Indeed one article described the very word as a ‘national heirloom…more precious than gold’.7‘Day By Day’, Daily Telegraph, 29 May 1916, quoted in Jo Hawkins, ‘Anzac for Sale: Consumer Culture, Regulation and the Shaping of a Legend 1915–21’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2015, p. 8 and p. 14 On 18 May 1916 the government passed a new statutory rule under the War Precautions (Supplementary) Regulations 1916 which prohibited the use of the word ‘Anzac’ ‘in connexion with any trade, business, calling, or profession’.8Statutory rule no. 97, War Precautions (Supplementary) Regulations 1916, 18 May 1916, ComLaw, accessed 26 March 2015 It noted:

In addition, over duration of the war, ‘Returned Soldier’, ‘Aussie’, ‘Our Wounded Soldiers’, ‘Repatriation’, ‘AIF’, ‘Australian Imperial Force’ and many other words were prohibited under the regulation.9‘’ANZAC’ – a national heirloom’, Gallipoli and the Anzacs, Department of Veterans’ Affairs and Board of Studies NSW, 2010, accessed 25 March 2015. See also ‘Our Wounded Soldiers Not to be Used as Trade Mark’, 9 February 1917, The Telegraph, p. 2 and ‘Prohibited Trade Mark’ 15 July 1919, Western Argus, p. 21

But just as the Prime Minister and his cabinet perceived the importance of the concept of Anzac, so too did business owners recognise the commercial potential of such a commonly held perception of Australian servicemen. Wrigley’s had trade marked their spearmint logo in July 1912.10Trade mark no. 13408, 26 July 1912, IP Australia via ATMOSS They claimed their product was a ‘great comfort to the soldiers in the trenches in Europe’ and called for Australian readers to ‘send some to your soldier boy!’.11‘Advertising’, 17 May 1916, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8

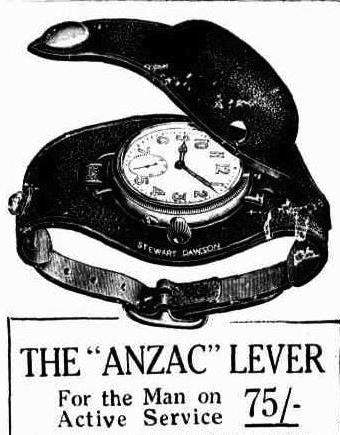

Before the regulation was introduced jeweller David Stewart Dawson advertised ‘“The Anzac” Luminous Dial Wristlet’ and ‘“Anzac” Lever’, a specially crafted watch ‘for the man on active service’, both of which were sold out of his store in Sydney’s Strand Arcade.12‘Advertising’, 22 September 1915, Sydney Mail, p. 32 and ‘Advertising’, 24 November 1915, Sydney Mail, p. 33 In June 1916, despite the recent introduction of the regulation, another Sydney advertisement included the ‘Anzac Lever’ in addition to an ‘unbreakable’ ‘Trench Mirror’ and ‘money belt’ for soldiers on the front.13‘Advertising’, 1 June 1916, The Catholic Press, p. 23 However, the watch appears to disappear from newspaper advertisements from the end of July 1916, likely because it contravened the new regulation.14‘Advertising’, 20 July 1916, The Catholic Press, p. 39

The New Zealander chemist, G W Hean, used a range of methods to advertise cough mixtures and nerve tonics for sale in his Sydney shop during the war. One 1916 notice included a jingle-like testimonial from one of Australia’s most famous poets, Henry Lawson: ‘Have some Horse Sense, Take Hean’s Essence – It’ll Rid Yer of that Corf, That’s a Cert’.15‘Advertising’, 9 November 1916, Punch, p. 31

On 22 July 1913 Hean’s trade marked their cough and cold remedy, Hean’s Essence, and began to use testimonials from serving members of Australia’s defence forces to promote their products from 1916.16Trade mark no. 15329, 22 July 1913, IP Australia via ATMOSS Master Sergeant P H Boag claimed he used the product and advises all his ‘comrades who catch cold to use Hean’s Essence without delay’.17‘Golds among our soldiers’, 24 June 1916, The Mirror of Australia, p. 4 Another advertisement stated an ‘epidemic of heavy colds’ was plaguing ‘our gallant soldiers’ and that Hean’s Essence was even warding off ‘attacks of the dreaded pneumonia’.18‘Coughs & Colds among our soldiers’, 1 April 1916, Cowra Free Press, p. 2 ‘A mother of soldiers’ Theresa Clune from Waverley said her sons Privates Francis and Jack Clune were ‘cured of heavy colds, contracted on their voyages from Gallipoli and America’.19‘Advertising’, 22 July 1916, Arrow, p. 3 The advert further asserted ‘thousands of Australian mothers’ were sending bottles of Hean’s Essence to ‘their soldier sons’.

On 5 October 1916 Hean’s registered another trade mark name for Hean’s Essence – ‘Heenzo’.20Trade mark no. 20657, 5 October 1916, IP Australia via ATMOSS Private Harley Cohen, a member of the musical group the ‘Gallipoli Strollers’, which comprised of servicemen injured at Gallipoli, wrote a poem:

…to part with all this Heenzo

Would have hurt a “digger” hard.

I’d have said, “This stuff is dinkum –

“Of it I’ve used a blinkin’ lot…”

I’ll make no bones about it,

But tell yer frank and free,

THE GALLIPOLI STROLLERS shook it…21‘Display Advertising’, 23 July 1918, The Argus, p. 6. See also ‘The Gallipoli Strollers’, 13 July 1917, Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, p. 7

An ‘original Anzac’ and chronic asthma sufferer, Lieutenant Angus McAskill wrote that his illness plagued him at the front and after he was invalided home, he ‘found nothing to equal Heenzo’ and considered it his ‘most faithful friend’.22‘Advertising’, 20 November 1918, Sydney Mail, p. 31 Twenty-two-year-old theatre actor and private in the 19th Battalion, William Paul Clare, noted he used Heenzo ‘for an over-worked throat while employed in open-air theatrical work’ and also during his service under ‘the greater contract’.23‘Advertising’, 24 November 1917, Weekly Times, p. 14

As demonstrated in the later advertisements Hean’s began including more elaborate recommendations which included photographs of real-life AIF servicemen, as if turning them into informal ‘poster boys’. Underlying their endorsements was the message that Hean’s was contributing in its own way to the war effort. Indeed one of their notices dramatically declared the ‘effects of a bad cold are almost as much to be feared as the shot and shell of the enemy’.24‘Colds among our soldiers’, 23 August 1916, Sydney Sportsman, p. 6 So with the often deadly spread of diseases including the common cold and influenza being a daily part of life in the trenches, Heenzo cough remedy was, in effect, saving lives.

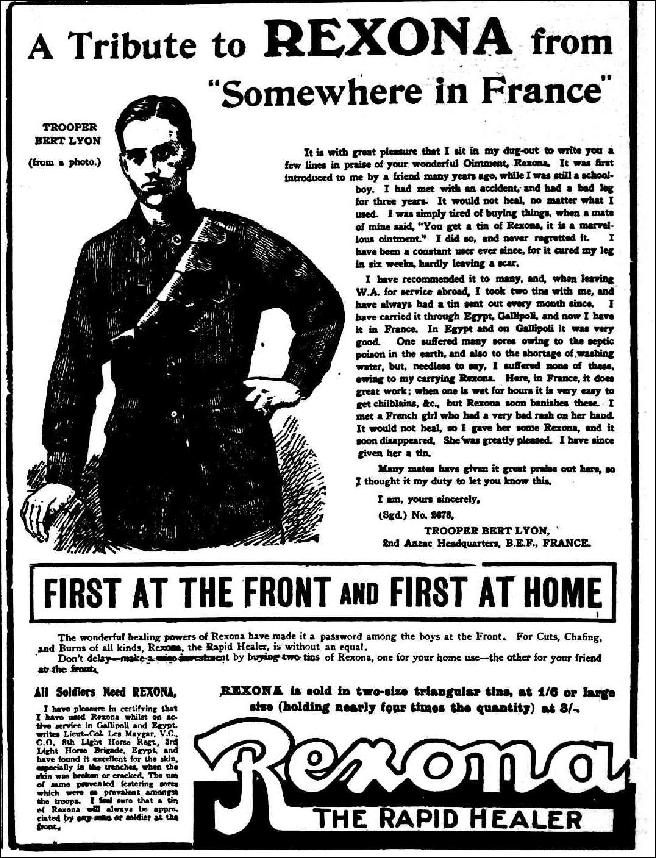

Advertisement for Rexona with a testimonial from ‘Trooper Bert Lyon’, 16 November 1918, The Advertiser, p. 13. Trove, National Library of Australia.

Hean’s was not the only business to use real-life “diggers” to promote their products. Rexona trade marked their ‘Rapid Healer’ in 1946, however, the ointment started appearing in advertisements as early as 1909.25Trade mark no. 85927, 31 January 1946, IP Australia via ATMOSS Advertisements claimed ‘Our Soldiers want Rexona – The Rapid Healer’ and asked readers, ‘Why don’t you send a Tin to the Front?’.26‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3 ; ‘Advertising’, 11 July 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 4 Private Stanley Roy Simpson stated he had seen enough ‘sores and wounds’ ‘to last me a lifetime, and I know what I am talking about…I can recommend Rexona Ointment heartily’.27‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3

These endorsements added a layer of credibility, as they did not just originate from a trustworthy source but also from the harshest of conditions. A group of AIF soldiers claimed they were ‘in the trenches in France…putting barbed out’ and requested ‘a few samples’ be sent.28‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3 One Lieutenant-Corporal Brookes adds with a certain Anzac flair, ‘All Australians prove themselves when put to the test. So does Rexona’ and that after being ‘blown up’ by a mine at Gallipoli used Rapid Healer on his shrapnel wounds.29 ‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3 In other advertisements, an artist drawing of ‘battle-scarred Anzac’ Bert Lyon of the 1st Battalion appears along with his appraisal which starts with: ‘It is with great pleasure that I sit in my dug-out to write to you a few lines in praise of your wonderful Ointment, Rexona’.30‘Advertising’, 16 November 1918, The Advertiser, p. 13 ; ‘Advertising’, 3 January 3 1917, The Register, p. 9 ; ‘Advertising’, 29 July 1918, The Advertiser, p. 6 He further notes that the conditions in the trenches often lead to ‘chilblains’ ‘but Rexona banishes these’.

In this sea of soldier testimonials, none appear published in print more frequently than that of ‘the crusader hero from Euroa district’, Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Cecil Maygar.31‘The late Lieut-Col Leslie C Maygar, VC’, 15 November 1917, Shepparton Advertiser, p. 3 Maygar was awarded the highest military award for valour, a Victoria Cross, in 1901 for rescuing a fellow Australian whose horse had been shot.32Elyne Mitchell, ‘Maygar, Leslie Cecil (1868–1917)’, 1986, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 31 March 2015 http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/maygar-leslie-cecil-7539/text13151 Described as a man with a ‘quiet, unassuming disposition’, Magyar was ‘an “Anzac” of whom Australia may be proud’.33‘The late Lieut-Col Leslie C Maygar, VC’, 15 November 1917, Shepparton Advertiser, p. 3 So with a testimonial from ‘a soldier who did not know the meaning of fear’, Rexona had a persuasive case to put forward for their product.34‘The late Lieut-Col Leslie C Maygar, VC’, 15 November 1917, Shepparton Advertiser, p. 3 Maygar’s testimonial was published in newspapers as early as August 1916, and under the heading ‘A Gallant Anzac Endorses Rexona’, he had ‘the pleasure in certifying that I have used Rexona whilst on active service in Gallipoli and Egypt, and have found it excellent for the skin, especially in the trenches’.35‘Display Advertising’, 25 August 1916, The Argus, p. 8

This use of the word ‘Anzac’ came to the attention of the Attorney General’s Department who objected to an ad in the Sydney Morning Herald in October 1917.36‘Advertising’, 27 October 1917, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 20 The Crown Solicitor deemed that the advertisement was referring to an actual soldier of ANZAC and not the idea of Anzac, so no further action was taken.37Item 29/3484, Part 17, A432/86, National Archives of Australia via ‘‘ANZAC’ – a national heirloom’, Gallipoli and the Anzacs, Department of Veterans’ Affairs and Board of Studies NSW, 2010, accessed 25 March 2015 Maygar died of wounds received from a German aeroplane bombing in Palestine on 1 November 1917.38Mal Booth, ‘Records of the death of Maygar VC’, 11 October 2006, Australian War Memorial blog. See also National Archives of Australia: B2455, MAYGAR LESLIE CECIL. It is unclear whether there were any further objections as the advertisement continued to be published, even up to two years after his death.39‘Advertising’, 4 November 1919, Mornington Standard, p. 4 ; ‘Advertising’, 2 January 1919, Daily Herald, p. 4 In any case, the roundabout use of the word ‘Anzac’ and an endorsement from one of Australia’s most prominent senior officers was a clever strategy from Rexona. As historian Jo Hawkins concludes, the inclusion of a decorated soldier meant ‘the product was truly fit for heroes’.40Jo Hawkins, ‘Anzac for Sale: Consumer Culture, Regulation and the Shaping of a Legend 1915–21’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2015, p. 23.

Conclusion

Communicated in the many trade marks registered and advertisements published during World War I, was the idea that the products on offer were integral to the war effort and that the brand behind them was unequivocally trustworthy. As they were endorsed by the likes of the country’s most reliable individuals of all, the brave men of Anzac, businesses were able to leverage this for commercial gain. In the business of product testimonials, who could be more credible and sincere than those men who were facing the most trying of circumstances? As with the early recognition and subsequent legal protection of this unshakeable idea of Anzac, it is clear brands like Wrigley’s, Hean’s and Rexona recognised the power of this source of approval for their consumers.

This article was originally published by IP Australia as part of a project to investigate IP rights during World War I. Read the original article. Reproduced here courtesy of IP Australia.

See also: Battlefront innovations and the ‘Engineer’s war’ and Symbols of support and the aesthetic of war

References

| ↑1 | See Jo Hawkins, ‘Anzac for Sale: Consumer Culture, Regulation and the Shaping of a Legend 1915–21’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2015, pp. 7-26. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ’Australians at Dardanelles: Thrilling Deeds of Heroism’, 8 May 1915, The Argus, p. 19 |

| ↑3 | ‘Battle of Gabe Tepe’, 23 June 1915, The Age, p. 13 |

| ↑4 | Charles W Bean, Anzac to Amiens, (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1983), p. 181 |

| ↑5 | ‘Australia’s Great Day’, 25 April 1917, The Advertiser, p. 7 |

| ↑6 | ‘Australia’s Great Day’, 25 April 1917, The Advertiser, p. 7 |

| ↑7 | ‘Day By Day’, Daily Telegraph, 29 May 1916, quoted in Jo Hawkins, ‘Anzac for Sale: Consumer Culture, Regulation and the Shaping of a Legend 1915–21’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2015, p. 8 and p. 14 |

| ↑8 | Statutory rule no. 97, War Precautions (Supplementary) Regulations 1916, 18 May 1916, ComLaw, accessed 26 March 2015 |

| ↑9 | ‘’ANZAC’ – a national heirloom’, Gallipoli and the Anzacs, Department of Veterans’ Affairs and Board of Studies NSW, 2010, accessed 25 March 2015. See also ‘Our Wounded Soldiers Not to be Used as Trade Mark’, 9 February 1917, The Telegraph, p. 2 and ‘Prohibited Trade Mark’ 15 July 1919, Western Argus, p. 21 |

| ↑10 | Trade mark no. 13408, 26 July 1912, IP Australia via ATMOSS |

| ↑11 | ‘Advertising’, 17 May 1916, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8 |

| ↑12 | ‘Advertising’, 22 September 1915, Sydney Mail, p. 32 and ‘Advertising’, 24 November 1915, Sydney Mail, p. 33 |

| ↑13 | ‘Advertising’, 1 June 1916, The Catholic Press, p. 23 |

| ↑14 | ‘Advertising’, 20 July 1916, The Catholic Press, p. 39 |

| ↑15 | ‘Advertising’, 9 November 1916, Punch, p. 31 |

| ↑16 | Trade mark no. 15329, 22 July 1913, IP Australia via ATMOSS |

| ↑17 | ‘Golds among our soldiers’, 24 June 1916, The Mirror of Australia, p. 4 |

| ↑18 | ‘Coughs & Colds among our soldiers’, 1 April 1916, Cowra Free Press, p. 2 |

| ↑19 | ‘Advertising’, 22 July 1916, Arrow, p. 3 |

| ↑20 | Trade mark no. 20657, 5 October 1916, IP Australia via ATMOSS |

| ↑21 | ‘Display Advertising’, 23 July 1918, The Argus, p. 6. See also ‘The Gallipoli Strollers’, 13 July 1917, Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, p. 7 |

| ↑22 | ‘Advertising’, 20 November 1918, Sydney Mail, p. 31 |

| ↑23 | ‘Advertising’, 24 November 1917, Weekly Times, p. 14 |

| ↑24 | ‘Colds among our soldiers’, 23 August 1916, Sydney Sportsman, p. 6 |

| ↑25 | Trade mark no. 85927, 31 January 1946, IP Australia via ATMOSS |

| ↑26 | ‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3 ; ‘Advertising’, 11 July 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 4 |

| ↑27, ↑28 | ‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3 |

| ↑29 | ‘Advertising’, 4 February 1918, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3 |

| ↑30 | ‘Advertising’, 16 November 1918, The Advertiser, p. 13 ; ‘Advertising’, 3 January 3 1917, The Register, p. 9 ; ‘Advertising’, 29 July 1918, The Advertiser, p. 6 |

| ↑31, ↑33 | ‘The late Lieut-Col Leslie C Maygar, VC’, 15 November 1917, Shepparton Advertiser, p. 3 |

| ↑32 | Elyne Mitchell, ‘Maygar, Leslie Cecil (1868–1917)’, 1986, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 31 March 2015 http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/maygar-leslie-cecil-7539/text13151 |

| ↑34 | ‘The late Lieut-Col Leslie C Maygar, VC’, 15 November 1917, Shepparton Advertiser, p. 3 |

| ↑35 | ‘Display Advertising’, 25 August 1916, The Argus, p. 8 |

| ↑36 | ‘Advertising’, 27 October 1917, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 20 |

| ↑37 | Item 29/3484, Part 17, A432/86, National Archives of Australia via ‘‘ANZAC’ – a national heirloom’, Gallipoli and the Anzacs, Department of Veterans’ Affairs and Board of Studies NSW, 2010, accessed 25 March 2015 |

| ↑38 | Mal Booth, ‘Records of the death of Maygar VC’, 11 October 2006, Australian War Memorial blog. See also National Archives of Australia: B2455, MAYGAR LESLIE CECIL. |

| ↑39 | ‘Advertising’, 4 November 1919, Mornington Standard, p. 4 ; ‘Advertising’, 2 January 1919, Daily Herald, p. 4 |

| ↑40 | Jo Hawkins, ‘Anzac for Sale: Consumer Culture, Regulation and the Shaping of a Legend 1915–21’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2015, p. 23. |